|

|

|

|

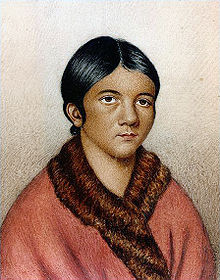

Shanawdithit

1801 – June 6, 1829

Beothuk

“Where today are the Pequot? Where are the Narragansett, the Mohican, the Pokanoket, and many other once powerful tribes of our people? They have vanished before the avarice and the oppression of the white man, as snow before a summer sun.”-Tecumseh

European Invasion of Northeastern North America

On June 24, 1497 John Cabot laid claim on behalf of England's King Henry VII to what thereafter would be called Newfoundland. The fact that the land was then owned and occupied by human beings, whose residency stretched back for millennia, was not viewed by Cabot or England as a legal impediment to this claim. In addition to appropriating another Nation's land, Cabot's explorations revealed for future European exploitation the region's fabulously endowed fishing grounds. These events soon led to a full-scale European invasion of northeastern North America.

In retrospect, the speed at which the news of the wealth of the Newfoundland and North Atlantic fishing grounds spread around Europe in an age without mass communications seems incredible. This news spread so fast and proved so alluring that within a very short period of time European fishermen began arriving en masse. By 1506, only nine years later, the fishery was so large that the Portuguese government was taxing it.

This uncontrolled and largely unpoliced foreign fishery would prove to be extremely bad news for the region's Amerindian peoples. In fact, the nature of the bad news was visited upon one Amerindian Nation almost immediately. The intruders launched a murderous assault on Newfoundland's harmless and non-aggressive Beothuk (or Red People) in retaliation for the "crimes" they were committing by removing items, such as nails, from the fishermen's fish-drying stations along the coast.

As early as 1506, many of the Beothuk were being sold as slaves in Europe. Many were simply slaughtered. Also, the assault caused traditional food supplies to be cut off, which led to starvation and malnutrition and made them prime candidates for contracting European and indigenous diseases, which, because of their malnutrition state, almost always proved fatal. In time, these barbarities led to the extinction of the Tribe.

The Beothuk spoke a Algonkian language, believed closely related to Mi’kmaq, and they and their ancestors had lived in what is now known as Newfoundland for thousands of years. They lived in small bands and lived off the abundant fisheries, shorebirds, and land and sea mammals, especially Caribou and Seals. It has been reported that they herded Caribou for slaughter into fenced areas. Altogether, an extremely healthy diet.

Population estimates of the Beothuk, as always, when made from a Eurocentric point of view, which seems to be geared toward diminishing the extent of the crimes against humanity committed against the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas by Europeans, goes from the ridiculous to the absurd, five hundred to a few thousand. My guesstimate, as they controlled a large landmass, would be somewhere in the vicinity of 25 to 50 thousand at the onset of the invasion in 1497. This had to be the case, after all, in spite of the ongoing efforts to exterminate them, it took three hundred and thirty three years to accomplish the genocidal deed - 1497 to 1829.

The leadership offices of the Nation was awarded to those who were honourable wise men. Decisions, as was the case for most North American First Nations, were by consensus. The were known as Red People because they mixed a red dye and coated themselves, and their belongings with it. Sharon O'Brien’s take on the practice: “The coating, which served as a symbol of tribal identity and initiation, may be the basis for the later European term ‘redskins’."

The Mi’kmaq have been accused of being responsible for the extermination of the Beothuk, which garbage is nothing but dehumanizing, demonizing European colonial propaganda. Some renegade members of the Mi’kmaq Nation may have been employed by the British - it wouldn't be the first time that people whose country was at war with an enemy colaborated with that enemy - to hunt the Red People, but there is no evidence whatsoever that the Mi’kmaq leadership ever made a decision to exterminate any race of people, let alone a race of people that many now believe were closely related to them. Another factor, which makes such an extermination alliance between the Mi'kmaq and the English unbelievable, is the fact that the Mi’kmaq were engaged in a one hundred and thirty year war with the English, a war that finally ended in 1761 at the Governor’s Farm in Halifax, where the Hatchet was buried, and Peace and Friendship treaties were signed. The Mi’kmaq did traditionally go to Newfoundland to hunt and fish, and ocassionally to help their French allies fight the English, and they often went to the Island when their food supplies on the mainland became scarce from over-harvesting.

"The tribe has vanished from the face of the earth; and the tale of their extinction forms an infamous stigma, a dark series of crimes, in the historic pages of both French and English colonisation." Anonymous

Daniel N. Paul

Beothuk_head

The following is quoted from a 1998 paper by Ralph T. Pastore, formely a teacher in the Archaeology Unit & History Department of Memorial University of Newfoundland.

“Prior to 1768, British naval governors and other officials took little notice of the Beothuks--probably because most Newfoundland settlers and migratory fishermen were little affected by them. In 1768, however, the naval governor, Hugh Palliser, sent Lieutenant John Cartwright up the Exploits River in an attempt to make contact with the (remaining) Beothuks and to draw them into a peaceful relationship with the English. Although Cartwright recorded numerous dwellings, he was unable to meet with any Indians.

In some ways, Palliser was representative of a new spirit in the Atlantic world. Increasingly, some members of society had become concerned about the casualties of western civilization. The anti-slavery movement, the movement to abolish judicial torture, and concern for the plight of Native people were all part of this growing humanitarian impulse. Palliser himself was concerned not only about the condition of the Beothuks, but also about that of the Labrador Inuit. He requested that Moravian missionaries come to Labrador, in part to help prevent conflict between whalers and fishermen on the one hand, and the Inuit on the other.

Unfortunately, this increased concern about the welfare of the Beothuks would have little real effect. In 1792 Captain George C. Pulling surveyed the English settlers on the northeast coast collecting accounts of atrocities perpetrated against the Beothuks and apparently submitted this report to a Parliamentary committee, although nothing of substance came of his efforts. A succession of governors, beginning with William Waldegrave in 1797, issued proclamations forbidding attacks on the Beothuks and offered rewards for making contact with the beleaguered people, but again with little positive result.

The most substantial attempt to contact the Beothuks occurred in the winter of 1811 when Governor John Duckworth sent Lt. David Buchan up the Exploits River accompanied by a small force of marines. Buchan surprised a large Beothuk camp whose occupants were probably paralyzed with fear. Buchan spent a short time with them during which he tried to convince them that his intentions were peaceful. Deciding to go back down the river for more presents, he left two of his men behind as hostages. Unfortunately, when he returned he found the camp deserted and his two men killed. It is probable that by this time the Beothuks had been so victimized that only the most extraordinary measures could have brought about a reconciliation between them and the settler population.

In the years after the Buchan expedition, settler populations continued to encroach on what had been Beothuk territory, and the Beothuks continued to raid fishing premises and furriers' cabins for European goods. Not surprisingly, the settlers retaliated. In 1818 a group of Beothuks cut loose a boat full of goods belonging to John Peyton Senior, a local entrepreneur who had long been known for his brutal retaliation against Beothuks who had taken his property. In the late winter of 1819, Peyton and a number of his men attacked a Beothuk village on Red Indian Lake and captured a young Beothuk woman after killing her husband. This woman, Demasduit, or Mary March, as her captors would call her, was sent to Twillingate and then to St. John's to meet the governor, who ordered her returned to her people. After a futile attempt to reunite her with the remaining Beothuks, she died aboard Buchan's vessel in January of 1820.

In 1823, three starving, sick Beothuk women surrendered to a Newfoundland settler living in Notre Dame Bay. They were brought to St. John's by John Peyton, Jr., the son of the man who had led the expedition which had captured Mary March. Ultimately, Buchan would try to return the women to their homes, but two died leaving alive a woman whom we know as Shanawdithit. Peyton Jr. took her into his household where she lived for five years, during which time it is quite possible that the small remnant left of her people died out. Shanawdithit was sent to St. John's in 1828 where she was interviewed at length by William Cormack, an explorer who had made two previous, and unsuccessful, attempts to make contact with the Beothuks.

Sadly, Shanawdithit died in St. John's in June of 1829. Her death probably marked the end of her people, and as such was a tragedy of terrible proportions. It is important to remember, however, that the demise of the Beothuks was not the result of “500 years of genocide” as some writers have claimed. Rather, it was the result of a complex mix of factors involving the island's unique ecology, history, and economy. The fact that there is no simple explanation for the extinction of the Beothuks in no way diminishes their loss and that of humanity's."

Statue of Shanawdithit

Boyd's Cove Beothuk, Newfoundland.

Quoted from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Shanawdithit (ca. 1801 – June 6, 1829), also referred to as Shawnadithit, Shawnawdithit, and Nancy April, was the last recorded surviving member of the Beothuk people of Newfoundland, Canada. An artist, she died of tuberculosis (TB) on 6 June 1829 in St. John's, Newfoundland.

She was born circa 1801 near a large lake in Newfoundland. At the time, the population of the Beothuk was dwindling. Their traditional way of life was affected by encroaching European settlements on the island and they suffered from infectious diseases. The Beothuk access to the sea, a major food source, was slowly being cut off. Trappers and furriers regarded the Beothuks as thieves and attacked them to keep them away. As a child, Shanawdithit was shot by a trapper while washing venison in a river, though she was not severely injured and recovered.

After the 1819 capture of Demasduwit, the aunt of Shanawdithit, the few remaining Beothuk people fled from the British. In the spring of 1823, Shanawdithit lost her father, who died after falling through the ice. Others of her extended family also died. Hungry and without protection, Shanawdithit, her mother and sister sought help from the nearest settler, a trapper named William Cull. The three women were taken to St. John's, Newfoundland. There Shanawdithit soon lost her mother and sister to TB, a disease for which there was no cure at the time.

The British renamed Shanawdithit as Nancy April, and took her to Exploits Island. There she worked as a servant in the household of John Peyton, Jr. and learned some English. Beginning in September 1828, she lived for some time in the household of William Eppes Cormack, a Scots immigrant and Newfoundland entrepreneur and philanthropist. He founded the Beothuk Institution to study the people and drew funds from it to help support Shanawdithit. He recorded much of what she told him about her people, and added notes to her drawings. Shanawdithit remained in Cormack's care until early 1829. Although the government hoped she would become a bridge to her people, she refused to accompany any expedition. She said the Beothuks would kill any Native who had had contact with the Europeans, as a kind of religious sacrifice and redemption for those who had been killed.

After Cormack left Newfoundland to return to Great Britain, he stayed for some time in Liverpool with John McGregor, a Scots immigrant whom he had known in Canada. Cormack shared with McGregor much of his materials on the Beothuks.[2] Shanawdithit was transferred to the care of the attorney general James Simms. She spent the remaining nine months of her life at his home.

In precarious health from consumption (TB) for a number of years, Shanawdithit continued to deteriorate. She was cared for by William Carson, who tended her in her last illness but had no cure. She died of tuberculosis in a St. John's hospital in 1829.

After her death, the hospital presented the skull of Shanawdithit to the Royal College of Physicians in London for study. The rest of her remains were buried in the graveyard of St. Mary the Virgin Church on the south side of St. John's, Newfoundland. In 1938, the Royal College of Physicians gave her skull to the Royal College of Surgeons; it was destroyed in damage from the German bombing of London of World War II.

In 1903 the graveyard was dismantled for railway construction. A monument on the site reads: “This monument marks the site of the Parish Church of St. Mary the Virgin during the period 1859 - 1963. Fishermen and sailors from many ports found a spiritual haven within its hallowed walls. Near this spot is the burying place of Nancy Shanawdithit, very probably the last of the Beothuks, who died on June 6, 1829.

Shanawdithit is well known to Newfoundlanders; in 1851, the local paper the Newfoundlander called her "a princess of Terra Nova." In 1999, readers voted her the most notable Aboriginal person of the past 1,000 years; she captured 57% of the total votes.

Click to read about American Indian Genocide