|

|

|

|

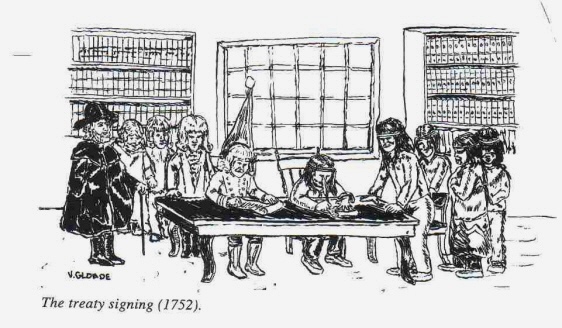

Signing

The Treaty of 1752 was signed on November 22, 1752 between governor Peregrine Thomas Hopson and Chief Jean Baptiste Cope.

Major Jean Baptiste Cope, Chief Sachem, of the Chibenaccadie Tribe of Mick Mack Indians, Inhabiting the Eastern Coast of the said Province, and Andrew Hadley Martin, Gabriel Martin and Francis Jeremiah, Members and Delegates of the said Tribe, for themselves and their said Tribe, their Heirs and the Heirs of their Heirs forever....

The treaty also contained all the demeaning provisions that the British had included in previous treaties. There were, however, the usual contradictions. For instance, the Colonial Council in 1749 had stated that it could not declare war upon the Mi'kmaq because to do so would be to recognize them as a free and independent people, yet Section 2 declares that this treaty ends the war.

Halifax Chronicle Herald - April 18, 2020

Land never ceded

I would like to comment on two aspects of Leo Deveau’s opinion piece “What does Reconciliation look like,” April 11.

First, Deveau suggests there is “no legal decision confirming that Nova Scotians live on unceded land.” He asks why people keep saying the traditional territory of the Mi’kmaq is “unceded.” In 1985, the Supreme Court of Canada dealt with this issue in the James Simon case. Simon, a Mi’kmaq from Sipekne’katik, relied, in his defence, upon a treaty made with the British in 1752. The province of Nova Scotia argued that only treaties under which Indians ceded land were applicable; the position of the province (correctly) was that the Treaty of 1752 was not a land cession treaty. The Supreme Court, while holding that the Treaty of 1752 did provide a defence, agreed that the Mi’kmaq did not cede land. The court stated: “None of the Maritime treaties of the eighteenth century cedes land.”

Historically, in most of Canada (Quebec, Ontario and the Prairie provinces), the land interest of Indian nations was surrendered to the Crown explicitly through land cession treaties. In Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Gaspe, the British made a series of treaties with Indian groups between 1725 and 1779. These 18th century treaties were treaties of peace and friendship, with reciprocal promises but no surrender or cession of land (or of hunting and fishing rights, for example). In modern times, Canada made comprehensive claim settlement treaties with some Indigenous people that included land cession, but such treaties have not been made with the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet or Passamaquoddy in the Maritimes or Gaspe.

Deveau also suggests that when the Mi’kmaq chiefs requested that Alex Cameron not represent the province on Mi’kmaw cases after the publication of his book Power Without Law, they opposed free speech and his right to publish his views. The Mi’kmaq did not ask that the book be banned or burned or that he was not entitled to his opinion. Rather, the chiefs were fearful that his personal view, namely, that the 1999 Supreme Court decision in Donald Marshall was wrongly decided, might influence the arguments he took to the courts on behalf of the province.

Our legal system is based on the principle of precedent: when the highest court in the land, the Supreme Court of Canada, speaks, judges and lawyers before the courts follow their decisions. In Simon and Marshall, the Supreme Court has spoken.

Bruce H. Wildsmith, Lunenburg County

Click to read an April 19, 1996 Hearld column about Chief Kopit: http://www.danielnpaul.com/Col/1996/Mi'kmaqChiefKopit-TrueHero.html

Click to read about Mi'kmaq Culture

Click to read about American Indian Genocide