|

|

|

|

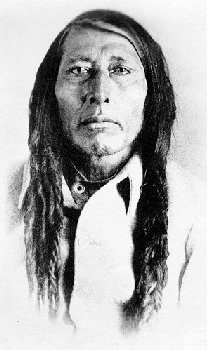

"We all know the story about the man who sat by the trail too long, and then it grew over, and he could never find his way again. We can never forget what has happened, but we cannot go back. Nor can we just sit beside the trail." Quoted from Canadian Government Website Visionary Cree chief and greatest hunter of his day, Poundmaker demonstrated his concern for the future of his people in his reluctance to accept Treaty # 6. Like his adoptive father — Crowfoot, Poundmaker counseled peace with the whites. In the face of growing frustration over government mismanagement culminating in the North-West Rebellion, he urged restraint, and was able to prevent further bloodshed at the battle of Cut-Knife Creek.

Quoted from University of Saskatchewan Libraries

Pitikwahanapiwiyin emerged as a political leader during the tumultuous years surrounding the extension of the treaty system and the influx of settlers into present-day Saskatchewan. Pitikwahanapiwiyin was recognized as a skilled orator and leader of his people by both Native and Non-native communities.

Born in about 1842 near Battleford in central Saskatchewan, Pitikwahanapiwiyin was the son of Sikakwayan, a Stoney shaman, and his Métis wife. Pitikwahanapiwiyin grew up with his Plains Cree relatives under the influence of his maternal uncle Mistawasis (Big Child), a leading figure in the Eagle Hill (Alberta) area. In 1873 Isapo-Muxika (Crowfoot), Chief of the Blackfoot, following a Plains Indian custom, adopted Pitikwahanapiwiyin to replace one of his own sons who had been killed in battle.

In August 1876 Pitikwahanapiwiyin, as headman of one of the River People bands, was influential enough to speak at the Treaty No. Six negotiations held at Fort Carlton. Pitikwahanapiwiyin emerged as one of the spokespersons for a group critical of the treaty. Though Treaty No. Six was amended to include a 'famine clause,' Pitikwahanapiwiyin continued to express concerns and agreed to sign the treaty on 23 August only because the majority of his band favoured it.

In the autumn of 1879, Pitikwahanapiwiyin, now chief, accepted a reserve and settled with 182 followers on 30 square miles along the Battle River about 40 miles west of Battleford. Frustrated by the government's failure to fulfill treaty promises, Pitikwahanapiwiyin became active in Indian politics: representing the Cree at inter-band meetings and acting as a spokesperson with the government. In July 1881 Pitikwahanapiwiyin acted as guide and interpreter during Governor-General Lord Lorne's trip from Battleford to Calgary. In June 1884, a Thirst Dance was held on the Poundmaker reserve to discuss the worsening situation of the Indians. By the middle of the month over 2,000 people had gathered. The Thirst Dance celebration was disrupted by the North-West Mounted Police pursuing an Indian accused of assaulting the farm instructor on an adjacent reserve. Violence between the Indian bands and the 90-man police force was averted by the peacekeeping efforts of Pitikwahanapiwiyin and .

When news of the Métis success at Duck Lake reached the Poundmaker reserve in March 1885, Pitikwahanapiwiyin decided to utilize the unrest and fears of government agents to negotiate necessary supplies. Joined by the Stonies, the Cree went to Battleford. Arriving on 30 March, Pitikwahanapiwiyin and his people found the town deserted. Efforts to open negotiations with Indian Agent Rae failed. Hungry and frustrated, some of Cree and Stonies began looting the empty homes in the Battleford area, despite Pitikwahanapiwiyin's attempts to stop them. The next day the combined Battleford bands moved west to the Poundmaker reserve and established a large camp east of Cutknife Creek. Though Pitikwahanapiwiyin was appointed the political leader and chief spokesperson for the combined bands, a soldiers' lodge was also erected at the Cutknife camp. According to Plains Cree tradition, once erected the soldier's lodge, not the chief, was in control of the camp.

attacked the camp in the early morning of 2 May 1885. After seven hours of fighting, the Indians forced Otter to withdraw. At this point Pitikwahanapiwiyin stepped in and stopped the Indians from attacking the retreating troops. Following the Battle of Cutknife Hill on 2 May, Pitikwahanapiwiyin attempted to move the camp to the hilly country around Devil's Lake. The warriors leading the camp, however, prevented this retreat and began leading the combined tribes east to join Riel at Batoche. On 14 May, while passing through the Eagle Hills, the Battleford bands captured a wagon train carrying supplies for Colonel Otter's column. Once again Pitikwahanapiwiyin successfully intervened to prevent bloodshed and the twenty-one teamsters captured along with the wagons were taken prisoner.

Five days later the Battleford bands learned of the Métis' defeat at Batoche. Regaining control of the combined bands, Pitikwahanapiwiyin sent Father Louis Cochin to asking for his peace terms. On 26 May, Pitikwahanapiwiyin surrendered his arms and his followers at Fort Battleford. He was immediately imprisoned.

On 17 August 1885 Pitikwahanapiwiyin's trial on the charge of treason-felony began in Regina before Judge Richardson. Regarded as second in importance only to Riel's, the trial lasted for two days. After deliberating for half an hour, the jury returned a guilty verdict. Pitikwahanapiwiyin was sentenced to three years in the Stony Mountain Penitentiary in Manitoba. He served only one year before being released because of poor health. Four months later, while visiting his adopted father Isapo-Muxika on the Blackfoot reserve, he suffered a lung haemorrhage and died.

(1842 - 1886)

http://www.collectionscanada.ca/2/6/h6-234-e.html

http://library.usask.ca:9003/northwest/background/pound.htm

For thier part in the Frog Lake Massacre the starving Cree, Wandering Spirit and five other warriors: Round the Sky, Bad Arrow, Miserable Man, Iron Body, Little Bear, Crooked Leg and Man Without Blood, were convicted of treason. They were hanged with two other Cree convicted of murder in the largest mass execution in Canadian history.

The First Nation People abiding around the area, living in various states of starvation and malnutrition, were forced to watch the executions. The following is what the Father of Confederation had to say about it:

20th of November, 1885 : In a letter to the commissioner of the Indian Affairs - «The executions of the Indians ought to convince the Red Man that the White Man governs.» - Sir John A. MacDonald, prime minister of the Dominion of Canada

More information about the Resistence can be found at the following addresses:

Louis Riel:

Chief Wandering Spirit:

Prime Minister John A. Macdonald's government oversees the mass execution of eight Cree:

President Abraham Lincoln's Administration permits the Mass execution of 38 Sioux:

American Indian Genocide:

Debunking ‘white man’s truth’

Siege of Battleford posters misrepresent history, argue aboriginals

By The Canadian Press

Fri, Aug 13 - 4:53 AM

The gravesite of eight aboriginal men who were involved with the North West Rebellion in 1885 is marked by a teepee in Battleford, Sask. (GEOFF HOWE / CP)

NORTH BATTLEFORD, Sask. — They call it the Siege of Fort Battleford, one of the best-known events of the Northwest Rebellion, and Parks Canada will re-enact it again this weekend from the point of view of the terrified settlers within the fort’s palisades.

But this year, the rebellion’s 125th anniversary, at least one aboriginal historian has had enough.

Tyrone Tootoosis points out there was no siege, just hungry and desperate people come to ask for help, and he’s tired of Parks Canada posters that present the encounter as an armed struggle.

"Our elders call this the white man’s truth," says Tootoosis, a member of the Poundmaker band, curator of the Wanuskewin cultural park in Saskatoon and performer who calls himself a story-keeper.

"Our people went (to the fort) because they were hungry. They were starving."

In the spring of 1885, what eventually became Saskatchewan was in turmoil as Metis and some Cree led by Louis Riel fought back against what they saw as settler encroachment on their lands. By the end of March, whites had already been killed at Duck Lake and Frog Lake and rumours were spreading like a prairie fire that Cree from chief Poundmaker’s band were massing to join the revolt.

Terrified, hundreds of people from the town of Battleford poured into the North West Mounted Police fort. Civilians were armed to add to the detachment of 25 Mounties and the fort’s stockade was beefed up for the attack settlers were sure was coming.

On March 30, the Cree came. But no attack followed.

Poundmaker asked to meet with the Indian agent, but his request was denied. For the next three weeks, 500 settlers and townspeople cowered inside the tiny fort while some Cree roamed the town, looting and burning several homes and emptying the Hudson’s Bay depot. Occasional shots were fired. A policeman was killed.

But the fort was never attacked or surrounded, nor was its surrender demanded. During the "siege," scouts from the fort often couldn’t find any Cree for dozens of kilometres around.

In fact, Poundmaker was there to ask for the supplies promised his people and to reassure the Mounties that he had no plans to join Riel.

So why, asks Tootoosis, does Parks Canada advertise its annual re-enactment with posters proclaiming Siege of Battleford, complete with pictures of soldiers aiming rifles and cannons?

"If there was no siege at Fort Battleford, what are they doing?"

Scott Whiting, director of Fort Battleford National Historic Site, agrees that "siege" doesn’t really describe what happened. But he says that’s not how it felt to the isolated settlers of Battleford. "There was a siege mentality. That’s what we’re representing."

During Saturday’s re-enactment, 15 vignettes taken from settler accounts will be acted out in an attempt to convey something of their isolation and fear. At the same time, tour guides will give visitors the full perspective unavailable to people at the time.

"One of the things we try to do is portray multiple perspectives on history," Whiting says.

Settlers didn’t know anything about Poundmaker’s intentions, he adds. In an age of difficult communications, all they knew was that area aboriginals had killed whites and a large party of Cree were massing nearby.

"They thought they were in grave danger," Whiting says. "It’s a very confusing time for everyone involved."

Whiting insists that the tour guides will leave nobody in doubt about what really happened.

Tootoosis says the audience for the re-enactment may get the whole story, but the people who just see the poster may be left with the impression of a Hollywood-style shoot-em-up.

"It doesn’t indicate on the poster the siege was in the minds of the settlers," he says. "They need to indicate that."

Whiting does acknowledge the "siege" of Battleford is widely misunderstood.

"It’s a story that’s not been well-told over the years and perhaps it hasn’t always been fairly told."

Click to read about American Indian Genocide