|

|

|

|

Wulustuk Grand Council News

February 25, 2005

Pat Paul's Tobique News Letter

I was born December 1938 in a small log cabin on Nova Scotiaís Indian Brook Reserve (approximately five miles away from the white village of Shubenacadie) to William and Sarah (Noel) Paul. My Mom told me in later years that I was born in a flash, as if I was in a rush to go somewhere. A doctor stopped by a few weeks after the fact to see how things were going. I was breast fed, and later fed Carnation Milk, that is, when we could afford it. I was an early convert to black tea. We were, at the time, a family of ten, with two more to come.

By the time I was two, we had moved into a new small uninsulated house that my father had built out of lumber he had acquired by trading labour for it with saw mill owners. It was standard Indian reserve housing of the day, no modern services of any kind.

Heat was provided by a wood burning kitchen range and a pot bellied tin stove. Our fuel was wood. My father often did chores for several white farmers who owned farms bordering the reserve. They would sometimes generously haul firewood out of the woods for him by horse and sleigh. However, on many occasions, he carried it out on his back. Our night light came from kerosene lamps, lanterns, and candles. The famous outhouse took care of the toilet department. I remember clearly unloading in the winter when it was below zero, and the old catalogues that passed as toilet paper. One did not sit long and contemplate life during the winter months, suffering a frost bitten behind was a real possibility. Although we had a well, the water was unfit to drink, drinking water had to be carried by hand from over a mile away.

Christmas dinners often consisted of stuffed porcupines, chicken sometimes, turkey never. It was mostly served with potatoes and gravy, and, when affordable, carrots and turnips. Toys delivered by Santa were often second-hand, or, handmade. Clothes were almost always second-hand. Old Mountie outfits often graced the backs of the men of the community. Bedding for our beds were the old army blankets passed out by the Indian Agent once a year, sheets were often made out of Robin Hood flour bags, and straw filled ticks made out of animal feed bags served as mattresses. Feet were the main mode of transportation. If memory serves me correctly, there was only one old car on the reserve at the time. Thus, food and kerosene had to be carried by hand from Shubenacadie, approximately 5 miles.

My Mother kept a spotless house. She scrubbed rough wooden floors on her hands and knees, and washed our clothes in a tub with a scrub board. The iron for pressing clothes, of course, was heated on the kitchen range. My Father, a small man physically, often walked more than five miles in one direction to earn some money to feed us. In the winter time, because he didnít have proper winter footwear, he would take old rags and wrap them around his feet before putting on his rubber boots and setting off to try to find work. Finding work had to be done in person, as we didnít have telephones.

In hindsight, I can say that our poverty was equivalent to what citizens of poverty-stricken Nations around the world suffer today. But, at the time, because we knew no other way, it seemed normal to us. Thus, those days were not without some pleasant memories.

I can still see us as a large family sitting around the lamplit table having supper - incidently, a table I often left hungry. This was caused by the fact we were very poor and there were so many of us - second helpings were the exception, not the rule. Soup bones often were recycled for a few meals.

Our toast was made by putting bread directly on the stove top and slightly burning it. We topped it with molasses, or jam, butter was a rare treat. I remember one winter night when we had a small piece of butter that Mom said we could have on our breakfast toast the next morning. As chance would have it an old man (he probably was only in his thirties, but when youíre very young anyone more than twenty is old) dropped in to visit that evening and was given lunch. We were all upstairs, supposedly in bed, but peeking down the heat hole that dad had cut in the ceiling to provide some heat upstairs. The visitor took a piece of bread and spread most of our precious butter on it. One of my sisters, without thinking, blurted out loud ďlook at that old bastard, he ate all our butter.Ē The comment was heard downstairs and she suffered an old fashioned switching for her disrespect. However, what she said was heartfelt, and I donít think she ever regretted it.

We finally got electricity in 1951. Shortly thereafter, at fourteen years of age, I ran away from home and went to Boston. It was there that I learned about the modern conveniences that much of society enjoyed. It was a case of a hillbilly going to town. For the first few weeks I would greet people on the streets with a hearty good morning. They responded by looking at me as if I had holes in my head!

I have, in spite of the poverty, so many pleasant memories of my youth that I could fill a book with them. Perhaps I will someday, but, because of space limitations, the before-mentioned will have to do for now.

However, before I finish, I want to mention some of the unpleasant experiences that we suffered because we were Indians. Indian agents, store owners, some doctors and other professionals treated us in a humiliating disrespectful fashion. Teachers taught us that we were descended from inferior cultures. We were barred from many establishments, not allowed to vote because we were classed as Wards of the Crown, with the same rights as drunks and insane persons, denied justice on all fronts, etc. One could be chucked in jail for disturbing the peace if he or she choose to argue with a white person. Combined, it gave us a monumental inferiority complex. Which, I can say from first hand experience, is extremely hard to overcome, but, try we must.

Today, we have the means to fight back and completely regain our dignity. Lets do it! Some say that they donít know anything, or enough, about the past mistreatment of our people to begin the process. To help overcome this deficiency Iíve written a history of the Miíkmaq Nation entitled, We Were Not the Savages, it reveals the abuses suffered in detail and will provide the knowledge needed for an informed fight for justice.

The following are a few of the items that we must demand that white society change forthwith:

IT must stop honouring Governor Edward Cornwallis, the man who issued proclamations in 1749 and 1750 for the scalps of First Nation men, women and children in the hopes of exterminating the Miíkmaq.

IT must repeal the scalp proclamation issued for Miíkmaq scalps in 1756 by Governor Charles Lawrence. I can assure you that if such a bounty for any race other than Indian was on the books it would be repealed tomorrow. In our case, they have no respect for us, thus they donít think itís repulsive to leave it be.

IT must start teaching factual First Nation history in schools and dump the whitewashed versions. This must include the genocide committed within the bounds of what is now Canada. Including scalp proclamations, deliberate spreading of disease, starvation, malnutrition, and in later times efforts to exterminate by assimilation. The hard cold facts to do so are easily available.

IT must afford us economic inclusion across the board

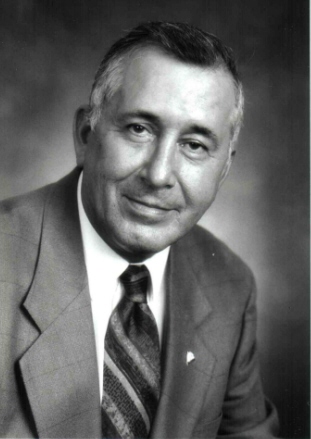

Daniel N. Paul

DANIEL N. PAUL