|

|

|

|

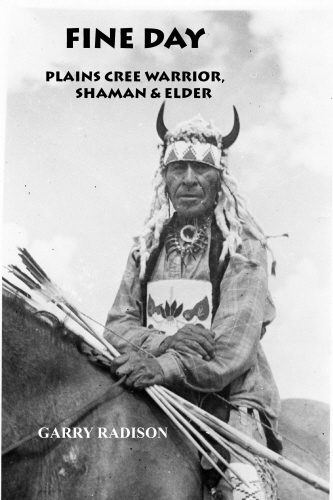

INTRODUCTION to FINE DAY: Plains Cree Warrior, Shaman & Elder

by Garry Radison (Published by Smoke Ridge Books).

Much of the history of western Canada has been told from the viewpoint of eastern Canada. The early history is often gleaned from the records of the Hudson’s Bay Company that itemized every trinket and fur but said little about the people who brought in those furs. When the immigrants arrived, the First Nations population was pushed to the side, their politics and culture disregarded. Even in the hundred and fifty years that followed, little was done to record indigenous western history.

Fortunately, in 1934, David Goodman Mandelbaum (1911–1987), an anthropology student from Yale University, came to Saskatchewan to gather cultural information about the Plains Cree for his thesis. Mandelbaum would go on to attain his doctorate and have a distinguished career in anthropology. He discovered that in Fine Day he had an eloquent informer with a vast knowledge of Cree culture, and in his well-known book, The Plains Cree, An Ethnographic, Historical and Comparative Study, he acknowledges Fine Day’s contribution. But throughout more than forty interviews with Mandelbaum, Fine Day scattered the details of his own experiences and thereby left us his personal history that is also the history of his people.

For much of the past 125 years historians who have touched on historical First Nations personalities have been content with repeating well known anecdotes or newspaper accounts. Most of these stories place the eastern newcomers at the center of these encounters. Hugh Dempsey’s Big Bear: The End of Freedom (1984) was one of the first (and best) books to present an important First Nations figure in the context of his own culture. The title of Deanna Christensen’s Ahtahkakoop: The Epic Account of a Plains Cree Head Chief, His People, and Their Struggle for Survival, 1816–1896 (Ahtahkakoop Publishing, 2000) speaks for itself. My own book, Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw ~ Wandering Spirit: Plains Cree War Chief, (Smoke Ridge Books, 2009) was the first full-length biography of this little known and grossly misunderstood war chief. Seen from the perspective of his own culture, Wandering Spirit emerges as a responsible leader whose first and foremost concern was for the safety of his band. Far from being the villain that Canadians portrayed him as being, he acted in good faith, erring only in not fully understanding the consequences of challenging the political and cultural pressures that were forcing the Cree into submission.

There are still other figures that deserve the attention of an astute biographer. With this present volume, I hope to address the neglect of historians who have deposited Fine Day on Cut Knife Hill on May 2, 1885, his experiences solidified into a cliché. Using only that moment, historian Grant MacEwan wrote a chapter, purportedly on Fine Day, but which, due to lack of information, detailed the life of Tecumseh, the Shawnee chief who fought with the British against the Americans in the war of 1812 and to whom Fine Day was often compared by eastern Canadians. By confining these figures to one moment in time, historians devalue the culture and falsify western history.

Western Canadian history is in need of re-visioning. There is more to the story than has been told by eastern Canadian historians, settlers and other writers working with eastern Canadian publishers. Much of what has been published in the past suffers from the prejudices of the writers whose only understanding of the Cree was derived from sensational novels depicting fictional Indians that probably never existed outside of the novelist’s head. James Clinkskill, who owned a store in Battleford in 1885 and who was present when Poundmaker’s Band surrendered, stated: “Looking at the crowd of Indians and contrasting their appearance with that described by [American novelist James] Fenimore Cooper, one could see how the race had deteriorated.”

Furthermore, since the settlers were newly arrived, the implication is that the perceived deterioration was caused by the Cree themselves and not by the Prime Minister’s starvation policy.

The language used to describe the events of 1885 has always been political and often reads like fiction. Louis Riel’s place in Canadian history has undergone several re-visionings from “rebel” and “traitor” to “martyr” and “hero.” Even the Canadian government is slowly accepting re-visioning the west. In 2010 Parks Canada agreed to drop the phrase “Siege of Battleford” acknowledging that a siege never occurred in 1885 and that the settlers misinterpreted their situation. The “Battle of Cut Knife Hill” is another loaded phrase that suggests the meeting of two opposing armies. It might more truthfully be called “The Unwarranted Attack on Cut Knife Hill.” In my attempt to view it as Fine Day experienced it, I have called the event “The Defense at Cut Knife Hill.” The Prime Minister of Canada and the Canadian government behaved badly in 1885, and, covering up their ineptitude and lack of humanity, they cast the Cree and other tribes in the role of villain. Their historians perpetuated the myths, occasionally throwing westward a bone of praise as a sign of conciliation.

The life of Fine Day (1856–1942) spans the period that saw the transition of the Plains Cree lifestyle from semi-nomadic hunters to settled farmers. Some Cree, mainly women and men who preferred to avoid war, perhaps found the transition less painful than the more adventurous hunters and warriors, though the transition was painful for everyone (and continues to be a problem today). Fine Day was one of the most adventurous men, a formidable warrior and accomplished hunter. Yet he eventually became a good citizen of the new Canada, a fairly successful reserve farmer and a respected elder. Always practical, he tried to find what was valuable in his environment and make good use of it. In the process of transition he did not forget his past or his culture and would not yield to the new masters, the Canadian Indian Agents, who tried to eliminate the Thirst Dance ceremony and other Cree customs. Perhaps his greatest legacy is the preservation of the Thirst Dance, often called the Sundance, to this day still the most important celebration of Cree culture. In most translations of Fine Day’s words, his reference to the ceremony is translated as “Sundance”, although Robert Jefferson uses “Thirst Dance” when translating Fine Day’s words in The Cree Rebellion of ’84. Though all aspects of the ceremony were important to Fine Day, he especially emphasized the importance of abstaining from drinking water during the four days of the ceremony. The Cree refer to the ceremony as “denying oneself water.” Therefore, I have taken the liberty in this narrative of altering those translations and using the phrase “Thirst Dance”.

Because of his status as a war chief in 1885, historians have made the assumption that Fine Day had made his reputation during the Blackfoot-Cree wars between 1860 and 1870 when the last major battle was fought. When he died in 1942, his obituary in the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix stated that the old warrior was 94 years of age, his birth date thus being 1848. Some writers have accepted this date; others, perhaps acknowledging a lack of documentation, have suggested a birth year in the early 1850s. If these dates are close to the truth, then Fine Day would have been able to participate in battles from about the age of 16; that is, from about 1864 or 1866.

However, Fine Day himself stated that there occurred four major battles between the Blackfoot and the Cree and that he had not participated in any of them. Though a warrior might miss a major battle for any number of reasons, to miss every battle raises questions. Why did Fine Day not participate in any of those battles? And where, then, did he acquire the warrior’s reputation for which he was later known?

The answer is simply that he was too young to participate in those battles. His birth occurred, not in 1848 as the newspaper claimed, but probably in the late fall of 1856. Being only fourteen when the last battle occurred in 1870, Fine Day, like every other boy his age, would have been excused from fighting; indeed, he would not have been allowed to accompany the warriors though there are indications that he probably wanted to.

A clue to his actual birth year was given by Fine Day himself in one of the Mandelbaum interviews. Fine Day stated that he was about ten years old when his father died. He associated his father’s death with another major event, a Cree attack on a Blackfoot village, which occurred at approximately the same time. A large Cree war party sought revenge for the deaths of Cree women who had been attacked by Blackfoot warriors in the spring. That winter the Cree warriors gathered and attacked. According to Fine Day, “The Blackfoot knew that a winter party would be a big one. They didn’t want to fight. They piled logs around their tipis. The Cree attacked. They fought two days. On the evening of the second day the Cree went off a little to eat.” The description of “logs piled around their tipis” and the fact that this was a revenge party are details that are extremely similar to the well known battle of December 3–4, 1865 when a Cree revenge party attacked a Blackfoot village that had been built within an enclosure of tree branches and brush.

Further evidence that Fine Day was born in 1856 is found in the 1901 and 1906 censuses where Fine Day’s age is recorded as 45 and 51 respectively. Though census records are notorious for being incorrect, the correlation with his memory of his father’s death strongly suggests that Fine Day’s birth year was 1856. After I had drawn that conclusion, I was pleased to discover that amateur historian Clayton McLain, who farmed near the Sweetgrass Reserve and knew Fine Day, had come to the same conclusion. That the birth occurred in late fall is suggested by Fine Day’s claim that he was born near Manitou Lake, near the western boundary of Saskatchewan, where his band would have been hunting buffalo before heading back east to winter.

The question of where and how he attained his warrior’s experience will be answered in the following narrative.

Historical narratives often lose some of their credibility when they use dialogue attributed to persons long dead. In this narrative, I do not invent any dialogue though some is used. These conversations come directly from Fine Day’s memory and though they may not be entirely accurate representations, they probably contain the gist of what was said. More importantly, they reflect Fine Day’s impressions of those events and personalities and therefore reveal something of his character.

In my book, Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw ~ Wandering Spirit: Plains Cree War Chief, I used Cree names as much as possible. Readers found that the multi-syllable names interfered with the flow of the narrative. In the present volume I have used, for the most part, the English translations. Where a name has alternate translations, I have, for consistency, selected one of the variations. For example, the name of Fine Day’s uncle, Kayatahkowit, has been translated as “Like A Star”, “Star Body”, and “The Star”. In this narrative I use “The Star”.

Fine Day’s name was Kamiokisikwew (Ka-mee-oh-kee-si-kwayo). He did not use the English version of his name though his descendants now use Fineday as the family name.

Kamiokisikwew can be translated as “fine day” or “fair weather”. But the phrase is not merely a comment on the weather. To the Cree whose lives had a sense of immediacy, an awareness of the present moment, a fine or beautiful day had connotations that life was good, that it was good to be alive, good to be part of the process of nature. In one sense, his name was a blessing.

GARRY RADISON is the author of five books of poetry. His poetic works have been described as “achingly honest...his unique voice, spare and muscular...resonates with the hard-earned truths of negotiating an unquiet peace with his prairie world.” (Hagios Press) The Saskatoon Star-Phoenix said his poems are “like guideposts in a vast desert.”

He has also written four works of non-fiction, two of which Wandering Spirit: Plains Cree War Chief, and Fine Day: Plains Cree Warrior, Shaman & Elder, are his attempt to bring to life the history of the west from the point of view of the people who lived there.

Born and raised in Saskatchewan, he and his wife now live in Calgary, Alberta. He can be contacted at: radisongarry@yahoo.ca

More information about the Resistence can be found at the following addresses:

Chief Poundmaker:

Louis Riel:

Prime Minister John A. Macdonald's government oversees the mass execution of eight Cree:

President Abraham Lincoln's Administration permits the Mass execution of 38 Sioux:

Click to read about American Indian Genocide