|

|

|

|

"We're happy that he's at peace now." Donald Marshall Junior Memorial Award

The Award is to commemorate Donald Marshall’s courageous and determined legal battle to exonerate himself of a racially motivated wrongful murder conviction. His tenacity, which saw him exonerated, and which provided the motivation for a complete overhaul of the antiquated Nova Scotia Justice system, and positive changes to Canada’s Criminal Justice system, provides an excellent example of human achievement! Also, for his contribution towards recognition of Aboriginal Treaty Rights.

The Award is to be awarded annually at the Dalhousie Schulich School of Law to a third year graduating student, who raises awareness of legal issues affecting Aboriginal Peoples, including Criminal Justice Reform"

If you would like to make a contribution to help fund the Award, please click Dalhousie Law, then click on the drop-down boxes under "area of support," touch the arrow and click on "Law," in the second box "Faculty of Law," will show, the following box touch the arrow and scrool down to "Donald Marshall Jr Memorial Award. Thanks for your support, most appreciated!

The recomendations of the Royal Commission on the Donald Marshall, Jr., Prosecution, in regards to his wrongful conviction, resulted in the Nova Scotia Government organizing a Court Restructuring Task Force to revamp the Province's antiquated Justice System. The Nova Scotia Court Structure Task Force Report was issued March 1991, virtually all of it's recomendations have been implemented. I, Daniel N. Paul, was the Mi'kmaw member of the Task Force.

A personal tribute to a man of great courage, the late Donald Marshall Jr.

The determination Donald Jr. and his late father, Grand Chief Donald Marshall Sr., displayed in proving his innocence and finding justice for him, throughout his wrongful conviction ordeal was rock solid, they never wavered. They finally persevered and, as history relates, Jr. was exonerated.

The outing of the systemic racism prevalent in Nova Scotia, and Canadian society in general, that was responsible for Donald’s wrongful conviction in 1971, has been, and still is, and will continue to be, the most positive outcome from his horrific ordeal. The revelations turned the Canadian and Nova Scotia justice systems on their heads, and caused major reform in both systems. The reforms have made it far less likely that another First Nation Person will be convicted in Canada of a major crime because of his/her racial origins.

For their courage in taking on a formidable opponent, Nova Scotia’s Justice system, and causing such great positive change in it, we owe Donald Jr. and Sr. a great debt. Springing from it we have a binding obligation to pick up the mantel and continue the battle against systemic racism until such time as it becomes a sour memory.

I have a suggestion to make, that I’m sure would honour Donald’s memory properly, and please him tremendously. There is a Cornwallis park in Halifax, which is named in memory of a British colonial Governor, Edward Cornwallis, who made an attempt to exterminate the Mi’kmaq, which could be renamed in his honour. It's continued existence with it's current name, because it is named in honor of a man who tried to wipe out a race of people of colour, is a symbol of the residual systemic racism that is still alive and well in this province, and a blight on the Province's good name. Changing it would be a signal by Nova Scotia that it is serious about ending forever systemic racism in the Province. Therefore, remove Cornwallis’s statue, install one of Donald Jr., and rename the park Donald Marshall Jr. Memorial Park. A fitting memorial to a man of great courage!

Donald has now departed to the Land of Souls, where he will keep company with the Great Spirit, and family members and friends who preceded him, in tranquility for eternity. Although he will be missed by family and friends, he will be with us in spirit forever!!

In 1971 Donald Marshall Jr. was charged, tried and convicted for a murder he didn't commit. He was guilty of only one thing, presumably not a crime, being a Mi'kmaq. The Marshall Report issued by the Royal Commission on the Donald Marshall Jr. Prosecution in December 1989 castigated the Nova Scotia justice system, and society in general, for the injustices carried out against an innocent and defenseless Mi'kmaq boy.

However, in the final analysis, it wasn't the justice system that failed Junior, it was society. For without the racism that was all too prevalent throughout the province, and country, the justice system would not have dared to do what it did to him in the first place. Hearing his appeal in the 1980s, the Nova Scotia Supreme Court Appeal Division's judges felt compelled to blame and humiliate Junior, telling him that he was the author of his own misfortune. Their opinion provides a measure of how deeply held society's racist views are.

As a human rights activist, I consider this case to be the most significant milestone in the battle for human and civil rights by First Nations Peoples during the Twentieth-Century. The most positive fallout in Nova Scotia from it has been the transformation of the Province’s antiquated justice system into a highly equitable modern system.

Daniel N. Paul

In response to my request, Anne Derrick, Q.C., Co-counsel to Donald Marshall Jr. at the Royal Commission of Inquiry into his wrongful conviction, offers the following comments about The Marshall Inquiry.

"On January 26, 1990, the Royal Commission of Inquiry on the Donald Marshall Jr. Prosecution released its much-anticipated report on Mr. Marshall’s wrongful conviction for murder. (Commissioners’ Report – Findings and Recommendations 1989) For the Mi’kmaq community the most significant finding of the Inquiry’s three years of work (public hearings, roundtables and independent research studies) was the conclusion reached by the Commissioners that Donald Marshall Jr. was "convicted and sent to prison, in part at least, because he was a Native person." The Commissioners described the evidence supporting this “inescapable conclusion” as “persuasive” and said, “That racism played a role in Marshall’s imprisonment is one of the most difficult and disturbing findings this Royal Commission has made.”

On May 28, 1971 Donald Marshall Jr., walking through Sydney’s Wentworth park, met up with Sandy Seale, a Black youth from Whitney Pier. Marshall and Seale were casually acquainted. Proceeding through the Park together they encountered two men who struck up a conversation. One of these men, Roy Ebsary, described by the Commissioners’ Report as “an eccentric and volatile old man with a fetish for knives” with no provocation or warning, fatally stabbed Sandy Seale in the stomach. He died on May 29, 1971. On June 4, 1971, Donald Marshall, only 16 and still living at home on the Membertou reserve was arrested and charged with non-capital murder. The Royal Commission of Inquiry found that the fact that “Marshall was a Native is one reasons why John McIntyre [the Sydney Police Chief heading the Seale murder investigation] singled him out so quickly as the prime suspect without any evidence to support his conclusion.”

Donald Marshall’s journey through the criminal justice process proceeded with breath-taking speed, unthinkable today. Arrested on June 4, 1971, his preliminary inquiry occurred in one day on July 5, 1971 and his trial was heard over only three days from November 2 – 5, 1971. The justice system took only that short time to convict Mr. Marshall, by then just 17, and sentence him to life imprisonment for a murder he did not commit.

Mr. Marshall’s wrongful conviction occurred because of police and prosecutorial misconduct, the incompetence of his defence counsel, perjured testimony, jury bias and judicial error. It took 12 years for his wrongful conviction to be overturned and a total of nearly 20 years to exonerate him because, as the Royal Commission of Inquiry found: “The criminal justice system failed Donald Marshall, Jr. at virtually every turn, from his arrest and wrongful conviction in 1971 up to – and even beyond – his acquittal by the Court of Appeal in 1983.”

Donald Marshall, Jr. never relented in his struggle to free himself and clear his name. His courage and resilience are a beacon of inspiration to all Canadians, and especially to First Nation Canadians who knew long before the Royal Commission report that justice in Canada has not been indifferent to colour or social status. The 82 Recommendations of the Royal Commission dealt with - wrongful conviction, - Mi’kmaq and the criminal justice system, - Blacks and the criminal justice system, - police and policing. The findings and conclusions of the Commission have been cited in subsequent Commissions of Inquiry, scholarly articles and by the Supreme Court of Canada. The struggle and integrity of Donald Marshall, Jr., has left an indelible mark on Canadian criminal justice.

Anne Derrick

April 10, 2003"

On February 7, 1990, the Nova Scotia government officially apoligized to Donald Marshall Jr. for his wrongful conviction.

To read the Royal Commission's Digest Report and Recomendations Click here:

September 13, 1953 - August 6, 2009

Donald's brother David - August 6, 2009

Honouring Donald Marshall Jr. - Catherine Martin - August 6, 2009

He was a friend to anyone who had the pleasure of meeting him. He was a true ambassador of Mi’kmaq Rights. He was a true Mi’kmaq leader who put his people’s needs first before his own. He had the skills of a true leader, a hunter, an avid fisherman, and gifted speaker. He was kind, humble, concerned, and always had the time to talk to people. He had compassion for humankind and was a good friend to many. He had a great sense of humor evident through the twinkle in his eye and heartfelt laughter.

But, first and foremost, he was the son of Caroline and Donald Marshall Sr. of the Mi’kmaq First Nation community of Membertou, Cape Breton, NS. His parents were his most loyal fans and never left his side during his early days when he was imprisoned for a murder he didn’t commit. They always believed in their son’s innocence and fought to get someone to help him fight this injustice. Steve Aronson, a Dartmouth based lawyer answered their cries for help and worked diligently with Junior to get him out of jail. They were successful. Donald Marshall’s eleven years of life in prison, away from his parents, his family and community, was over. He lost a great deal during those years including the opportunity to learn from his father, the Grand Chief of the Mi’kmaq Nation.

Junior fought many battles in his life. An inquiry into his wrongful conviction created a basis for others in the country to find justice for wrongful imprisonments. The recommendations from the report on the inquiry has changed the course of the NS Justice system and created a somewhat better system for those who are marginalized and discriminated against in our society due to their race.

After settling into a life of new found freedom, Junior went fishing and was arrested for fishing eels out of season. This sparked the beginning of a legal battle that would eventually see the Supreme Court of Canada Decision affirm the Aboriginal rights of members of the Mi'kmaq First Nation, and members of Mi'kmaq First Nation Allies, to hunt and fish as usual, as they did prior to European invasion. The decision was second guessed by Canada and then revised by the SCOC, which somewhat altered the decision. This sparked a major battle between the Mi’kmaq, non-native fisherman, and the Canadian government.

Junior’s greatest battle was for his own life, as he endured a double lung transplant several years ago. His health has deteriorated over the years due to complications from the transplant. In spite of his failing health, Junior continued to work within the communities, especially with youth to create better lives for the people. He had run a youth survival camp for many years because he believed in helping youth find positive directions in their lives.

To those of us who loved him and believed in him, he will be sadly missed. To his mother and family, thank you for sharing your son and brother with the world, especially with the Mi’kmaq Nation. There is no doubt that his journey to the other side will be a good one, especially as he joins his father, the late Grand Chief Donald Marshall Sr and his sister Donna who are with the creator. This world is a better place because of Junior Marshall. This world will never be the same without Junior Marshall.

Wela’lin Junior. We wish you peace. M’sit Nokamaq.

New York Times - Obituary

August 7, 2009

Donald Marshall Jr., Symbol of Bias, Dies at 55

By WILLIAM GRIMES

Donald Marshall Jr., a Mi’kmaq Indian whose wrongful conviction for murder became a cause célèbre in Canada, leading to a sweeping re-examination of Nova Scotia’s legal system and changes in Canada’s evidence disclosure rules, died Thursday in Sydney, Nova Scotia.

He was 55 and lived in Membertou, Nova Scotia.

His sister, Roseanne Sylvester, confirmed his death, telling The Canadian Press that he suffered from kidney failure, which she linked to antirejection drugs he had been taking since a double lung transplant six years ago.

Late on the night of May 28, 1971, Mr. Marshall and a friend, Sandy Seale, went walking in a Sydney park and tried to rob an older man, Roy Ebsary, who drew a knife and killed Mr. Seale. (See New York Times withdrawal of this statement at the bottom of the page) Disregarding Mr. Ebsary as a suspect, the police decided that Mr. Marshall, known to them from previous run-ins, had killed his friend in an unexplained fit of rage. A jury agreed, and Mr. Marshall began serving a life sentence.

He was released from prison in 1982 after the Royal Canadian Mounted Police reviewed his case, and a year later the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal declared him not guilty of the murder. In its ruling, however, the court stated that Mr. Marshall was “the author of his own misfortune” and that there had been no miscarriage of justice.

A royal commission of inquiry later criticized that finding as “a serious and fundamental error.” In a seven-volume report delivered in 1990, it said police incompetence and “systemic racism” infecting the police department, the court system, the government bureaucracy and even Mr. Marshall’s own lawyers were to blame for the conviction.

“The criminal justice system failed Donald Marshall Jr. at virtually every turn, from his arrest and wrongful conviction for murder in 1971 up to and even beyond his acquittal by the Court of Appeal in 1983,” the report stated.

A subsequent Supreme Court case, citing Mr. Marshall’s ordeal several times, led to changes in evidence disclosure rules. Prosecutors had withheld information from the defense in the Marshall case, judging it irrelevant. The prosecution and the defense must now share evidence fully, regardless of their opinions on its relevance to a case.

The Marshall case became the subject of a book, “Justice Denied” (1986), by Michael Harris, and a 1989 film of the same name.

“It was the first commission of inquiry into a wrongful conviction in Canada,” said Anne Derrick, a provincial judge who, as a lawyer, represented Mr. Marshall during the Royal Commission’s work. “It stripped away a lot of the assumptions that people had about the criminal justice system.”

In 1993 Mr. Marshall was arrested and charged with fishing for eels out of season and without a license. In 1999, ruling on a case in which Mr. Marshall was the primary petitioner, the Supreme Court affirmed the centuries-old treaty rights of the Mi’kmaq and Maliseet in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia to earn a living from hunting, fishing and gathering.

Mr. Marshall, known as Junior, was one of 13 children of Donald Marshall Sr., who later became the grand chief of the Mi’kmaq nation.

Mr. Marshall continued to face legal troubles after his famous court cases. In 2006 he was charged with attempted murder for driving over a man after a New Year’s Eve party. Charges were dropped after Mr. Marshall and the other man agreed to take part in a ritual known as a healing circle. At the time of his death, he faced charges that he had assaulted and threatened his wife, Colleen D’Orsay.

For most Canadians, however, he remained the living symbol of a terrible miscarriage of justice.

“I can remember the day the commission’s report came out, and I told Junior Marshall he was exonerated,” Ms. Derrick said Thursday in a telephone interview. “It was as though a huge boulder had been lifted from his shoulders. He waited a long time for that.”

New York Times, Donald Marshall Jr. Obituary Correction:

"An obituary on Aug. 7 about Donald Marshall, Jr., whose wrongful conviction for the 1971 murder of a friend and exoneration 11 years later led to a re-examination of Nova Scotia’s legal system and changes in Canadian rules of evidence, misstated the circumstances that led to the friend’s killing, which had actually been committed by an elderly man they had encountered in a park. While Mr. Marshall admitted he was with his friend during that encounter, he withdrew an earlier admission that they were trying to rob the elderly man; Mr. Marshall was never charged with robbery. The obituary also misstated a change in rules of evidence resulting from the case. The prosecution must now fully disclose to the defense any evidence it has; the defense must ensure that full disclosure from the prosecution takes place, and must fully disclose its own evidence only in establishing alibis. The rule change does not mean that both “the prosecution and the defense must now share evidence fully.”

Globe and Mail Thursday December 31, 2009

Ten who made a difference - Part II

Stock-taking, the process of assessing who and what mattered in the past 12 months, is an inevitable stage in mourning the past and facing the future. Today is the final instalment of a feature by SANDRA MARTIN that began yesterday, remembering 10 people who died in 2009. Some of them are famous around the world, some are only known within our national borders, but all of them left the world a different and a better place. SANDRA MARTIN

Donald Marshall, 55 A proud Mi'kmaq, Donald Marshall was the torchbearer in two essential legal struggles in this country: justice for the wrongfully convicted and recognition of the historic treaty rights of aboriginal people. A big, rowdy kid, convicted of murder when he was only 17, he spent more than a decade in prison for a crime he didn't commit. Another eight years passed before he was exonerated by a royal commission, called by then federal justice minister Jean Chrétien. The commission, which recommended the overhaul of the entire provincial justice system in Nova Scotia, found that Mr. Marshall was the victim of racism and incompetence by a criminal justice system that had failed him "at virtually every turn from his arrest and wrongful conviction for murder in 1971 up to and even beyond his acquittal by the Court of Appeal in 1983."

Mr. Marshall broke the trail for other wrongfully convicted people, including David Milgaard and Guy Paul Morin, but his arrest and incarceration robbed him of his youth. Despite the tragedies of his later life - addictions to alcohol and cigarettes and troubled romantic relationships - he was also a hero in the battle against racism toward aboriginals in this country. He spent six years challenging the federal government's denial of the historic treaty rights granted to his people by the British Crown after 1760, a case that went to the Supreme Court of Canada.

********************

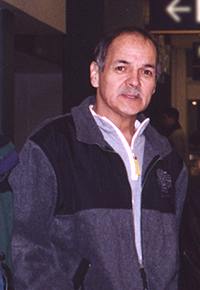

Donald Marshall

speaks to reporters on the day he was acquitted.

(Photo - ALBERT LEE / CP)

Halifax Herald - Published: May 23,2010

Marshall’s unsung hero

Lawyer proud of his place in history, but content with anonymity

By Becky Rynor

IT IS MOST likely to happen in what Stephen Aronson colloquially calls "Indian country." Those are the circles where the slight, soft-spoken Jewish lawyer is still remembered as the man who got Donald Marshall Jr. out of prison after serving 11 years for a murder he did not commit.

Aronson generally finds any attention for his part in what remains one of Canada’s highest-profile wrongful conviction cases, "a bit embarrassing," he says quietly. "Sometimes it’s more important to other people than it is to me."

In 1971, Marshall was convicted of murdering his friend, Sandy Seale, in a park in Sydney. He was just 17 when he was sentenced to life in prison. He was released in 1982 after the case was reviewed, thanks to what Judge Anne Derrick says was Aronson’s "lonely struggle" to have the Mi’kmaq man’s name cleared.

Now a Halifax provincial court judge, she was one of several lawyers who represented Marshall before the Royal Commission into his wrongful prosecution. She also represented him at the Royal Commission that reviewed his compensation, and with Archie Kaiser, acted for Marshall at the Canadian Judicial Council’s inquiry into the remarks made by the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal at the time of Marshall’s 1983 acquittal.

She is frequently mistakenly referred to as the lawyer who helped Marshall walk free.

"He’s an unsung hero, for sure," she says of Aronson. "But for Mr. Aronson, I don’t know how Mr. Marshall ever would’ve got out of prison. There was nobody else to step up to the plate for him. He had been buried alive."

"Can you imagine if Donald Marshall had cold called some lawyer and said, ‘I’m an aboriginal man, I’m locked up in prison and I’ve been wrongfully accused of murder, I want you to help me get out.’ There wouldn’t have been a whole lot of lawyers who would do this."

Aronson is originally from Montreal but grew up in Halifax. He was working in Halifax for the Union of Nova Scotia Indians when Marshall’s case came to him in 1981, "as a lawyer of last resort." He was 31 when the native advocacy group asked him to review Marshall’s preliminary hearing, trial transcripts and an appeal decision.

He was also asked to look into a confession by another inmate who claimed to have committed the stabbing. "That took an incredible amount of work, frustrating work, difficult work," Derrick says. "So for someone in a very small practice with ongoing overhead, this must have been a very great burden."

Aronson acknowledges there were months where he didn’t see a penny for the hours he poured into Marshall’s case. At the time he and his wife had an infant and a toddler and, "mostly lived off my wife’s salary. I think I paid for the groceries," he says.

While there were "definitely" times when he thought he was in over his head, he says he never considered dropping the case, though he had no idea of the legal proportions it would take on.

In 1982, Ron Fainstein was a senior general counsel in the federal justice department when Aronson brought him the submission requesting the Marshall case be re-examined.

"I had never seen a more complete submission," he recalls of the material Aronson put before him. "It was all there. Obviously he had put in an extraordinary amount of work."

He says he was equally impressed by the lawyer in front of him.

"He wasn’t there to do a job of advocacy. He wasn’t just arguing a position for someone he was hired to represent. He truly believed in what he was doing and that really shone through in the way he conducted himself. It was a very infectious thing."

His argument was so convincing that the justice minister at the time, Jean Chretien, recommended the case be re-opened. It was sent to the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal, which acquitted Marshall in 1983.

But Derrick says the victory was "tainted" by comments made by the Court of Appeal, blaming Marshall for being the cause of his own misfortune.

"This was just a very inappropriate exoneration of the system, she says. "It would have been a very bitter taste in (Aronson’s) mouth at the end of it all to have his innocent client who had 11 years of his life taken away from him, still saddled with responsibility for having got himself convicted in the first place."

But Aronson’s work paved the way to two Royal Commissions and a Judicial Inquiry into the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal’s statements.

"I think that to me in a lot of ways that was the best part of the whole thing," Aronson says. "It opened the system of justice to public scrutiny. I think it’s important for the public to have a better understanding of how the administration of justice does work."

"The Royal Commission said those remarks from the Court of Appeal were wrong and Mr. Marshall was not responsible for what happened," Derrick says. "It was the system that failed him, and it failed him in part because he was an aboriginal. So racism contributed to his wrongful conviction. That was hugely significant."

By the time Marshall was declared innocent, Aronson had been offered a job with the Department of Indian Affairs in Ottawa. And he took it.

"I was just tired. Tired physically and mentally and I just needed a change," he says. He also needed to make some money.

Aronson recalls he got paid about $74,000 in 1984, which he agrees was "probably" a drop in the bucket. "At the time it probably mattered more than it does today."

But he says he was ready to move on.

"I felt I’d done my part. He had been acquitted. I also felt it was just one part of a longer process which also included compensation and a commission of inquiry."

Aronson still lives in Ottawa, now running a private practice dealing exclusively in aboriginal law. He shrinks under any attention and one can only wonder how he survived being at the centre of a landmark legal case as well as the financial and emotional wounds it inflicted.

Today, when he recalls the Marshall case, he says the word that springs to mind is "tragedy."

"The fact that it happened in the first place is tragic. There were other victims, not just Junior. The witnesses were victims."

And he says a lot of people walked away with scars, including him.

"It was a pretty traumatic experience to go through. High stress, high pressure."

When Donald Marshall Jr. died in August 2009, accolades for the native man flowed.

"His name should go down in history as a sympathetic individual who had the rights of the Mi’kmaq people close to his heart," Chief Lawrence Paul of the Millbrook First Nation said at the time.

Many feel the same tribute could be said of Stephen Aronson.

"He conducted himself to the absolute highest standards of the legal profession," Derrick says. "He was prepared to take on a really hard case. It wasn’t like there was a whole bunch of support around of any kind at all. He did it and he did it to a very high standard. And Mr. Marshall walked out of prison a free man because Stephen Aronson did the work it took to make that happen."

In the years following the Marshall case, Derrick says she received a "cold call" from an aboriginal man in prison, claiming he had been wrongfully convicted of murder. And she took it.

"I took that call because I thought, ‘Stephen Aronson would take the call.’ Stephen Aronson’s example was a very concrete reference point to say, yeah, one does have this professional responsibility."

Becky Rynor is a freelance writer based in Ottawa.

*********************

Caroline (Kalo’lin) Marshall-Hobbs

Cape Breton Post

Caroline (Kalo’lin) Marshall-Hobbs - Born In: Waycobah First Nation, September 15th, 1928 - Passed in: Membertou on December 24th, 2014

Heaven welcomed a beautiful angel on Christmas Eve morning. Our dear mother and matriarch of our family Kalo’lin Marshall passed away peacefully with her beloved family and friends by her side.

Born Sept. 15, 1928, in Waycobah First Nation, she was the daughter of the late John P. and Madelaine (Gould) Googoo.

She was a devoted and loving mother who is survived by her loving children, Roseanne (Joe) Sylvester, Caribon Marsh, Josephine (Chris) Laporte, Membertou, Laura (Wade), Coxheath, Donna and Virginia (Donnie), Membertou; sons, Pius (Doreen), David (Terry Lynn), Terry (Lee), John, Simon (Adrianna), Stephen (Sheila), Membertou. She is also survived by her only sister, Josephine (Joe) Peck, Wagmatcook. She has 36 grandchildren; 43 great-grandchildren; two great-great-grandchildren; many nieces, nephews and several godchildren; best friend, Viola Christmas; daughter-in-law, Colleen.

Kalo’lin was a foster mother to many children.

Kalo’lin was predeceased by her husband, Grand Chief, Donald Marshall Sr., daughter, Donna and son-in-law, Stephen Gould, son, Donald Marshall Jr., daughter, Bernice, daughter, Margaret Madelyn in infancy, sisters, Susan Prosper, Emily Googoo and brothers, Peter, Angus and Stephen Googoo, second husband, John Hobbs, daughters-in-law, Martha (Denise) and Renee. She was a former member of St. Anthony Daniel Church and St. Ann’s Mission Church, Membertou, where she was a choir member for many years. Kalo’lin looked forward to attending the annual St. Anne’s Mission in Chapel Island where she personally celebrated her devotion to St. Anne, our patron saint.

In her early years she worked as a home-care worker and also at St. Rita’s Hospital. She also enjoyed and found time to bowl. Her whole life was devoted to volunteer work and helping people through sickness and hard times. Kalo’lin was a true elder and a friend to everyone, young and old. She will be dearly missed by her community.

She never lost faith in god and faithfully lived her life the way God would want all of us to. Kalo’lin received many awards throughout her life, including Membertou Citizen of the Year Award, Atlantic Aboriginal Entrepreneur Award and the Lifetime Achievement Award Caroline Marshall (basket maker). She was proud of the opportunity she had to make head dresses for several dignitaries as well as sharing her knowledge and skills of basket making with many generations.

Special thanks to the CCA in Membertou who cared for Kalo’lin for the past few years and the staff of 4B at the Cape Breton Regional Hospital for their care and support.

Visitation will begin at her home, 53 Bradley St., Membertou on Sunday, Dec. 28 after 7 p.m. Funeral mass will be celebrated at 10:30 a.m. Tuesday, Dec. 30 at St. Marguerite Bourgeoys, Rev Bill Burke will officiate. Interment in Membertou Memorial Gardens, Membertou. A salitP will follow at the Membertou Trade and Convention Center.

Donations in Kalo’lin’s memory may be made to St. Anne’s Mission, Membertou or a charity of choice.