|

|

|

|

TERRIFIED TWENTIETH-CENTURY EDUCATION

Shubenacadie Indian Residential School

FOR NATIVE AMERICANS IN

INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS

Cultural Genocide

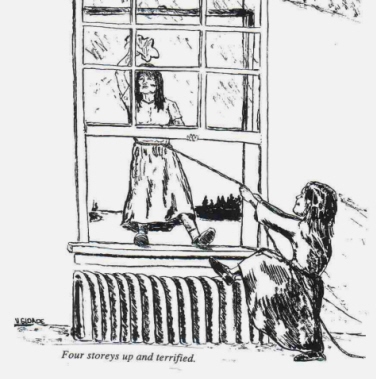

TERRIFIED A picture of Canadian Indigenous Children being seized by the RCMP

to be placed in Indian Residential Schools - Painting by Kent Monkman

June 27, 2020

A caution to the RCMP by Calvin Lawrence: Lawrence is a Black man who is a retired 28 year Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) officer and Author of Book entitled "Black Cop" 2019.

Leaders of the RCMP should remember that their history is grounded in the pain and suffering of First Nations people. Think of the pain of your children being dragged away crying by uniformed members of the force, to be held in Christian internment camps called Residential Schools.

When I was hired by the RCMP in 1978 the Noose that hanged Louis Riel was on display ?at RCMP Depot Training Academy in Regina.

All the good faith that was gained in First Nations communities over the years by the RCMP can be lost in a fast minute with the actions of one abusive police officer.

Twentieth Century Forcible Child Transfers: Probing the Boundaries of the Genocide Convention, By Ruth Amir PhD, Max Stern Yezreel Valley College, Nazareth, Israel, Department of Political Science. I wrote the following for the back page of her book after reading it.

"A well researched report about the horror of "legal" child abduction by the State, which deems itself the savior that will elevate the children of what it deems inferior cultures to it's notion of 'civilized' heights. Slay their children, or rob them of their cultural heritage by removal, the end result is Genocide."

“I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone… Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill.” Dr. Duncan Campbell Scott - 1920

Scott made his mark in Canadian history as the head of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932, a department he had served since joining the federal civil service in 1879.

Even before Confederation, the Canadian government adopted a policy of assimilation (actually, it was the continuation of a policy that British colonial officials had pursued since 1713). The long term goal was to bring the Native peoples from their ‘savage and unproductive state’ and force (English style) civilization upon them, thus making Canada a homogeneous society in the Anglo-Saxon and Christian tradition.

In 1920, under Scott's direction, it became mandatory for all native children between the ages of seven and fifteen to attend one of Canada's Residential Schools.

Quoted from We Were Not the Savages:

"In 1936 a fifteen-year-old girl from the nearby Shubenacadie Reserve refused to return to the school and gave the following statement to the agent and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police:

"I have been going to Indian school for the past five years.... Before my holidays this year I was employed in kitchen for eleven weeks.... In the eleven weeks ... I spent a total of two weeks in school. The Sister has beaten me many times over the head and pulled my hair and struck me on the back of neck with a ruler and at times grabbed ahold of me and beat me on the back with her fists.

I have also been ordered to stand on the outside of the windows with a rope around my waist to clean windows on the fourth floor with a little girl holding the rope. When I told the Sister I was afraid to go out the window she scolded me and made me clean the window and threatened to beat me if I did not do it. This is being done to other children.

After we get a beating we are asked what we got the beating for and if we tell them we do not know we get another beating. The Sisters always tell us not to tell our parents about getting a beating."

Although available on paper, education, a vital tool to provide First Nations citizens with the ability to appreciate and modernize their ancient cultures, was all but denied until recent times. This unwritten requirement of White society: "You may have an education, but only if you agree to assimilate and accept the eventual extinction of your culture." Plus, the racism encountered by students attending White schools made an education practically unattainable.

In spite of these impediments, through the efforts of private organizations and churches, by 1867 some First Nations Peoples were able to read and write. However, after Confederation, even in the knowledge that the vast majority of Natives were illiterate, the government made no real effort to provide education until the passage of the Indian Act in 1876. Then, it was made unattractive by the provision that automatically enfranchised a Band member who graduated from university. Assimilation was the motivating factor behind these laws.

To hurry assimilation along, during the first six decades of twentieth century, First Nations tongues came under attack across the country. In Nova Scotia, Mi'kmaq children were forbidden to speak their language at schools and discouraged to do so in many other public places. Administrators at the Shubenacadie residential school informed Mi'kmaq and Maliseet children upon enrolment that it was a cardinal offense to speak their own languages. If caught, retribution was swift.

The same rule was followed and strictly enforced by bureaucrats administering schools and other public institutions in First Nations communities across Canada. But nowhere was it pursued with the same dogged determination as on mainland Nova Scotia. This was not unusual, because from the time the British took over in 1713, the Mi'kmaq of peninsular Nova Scotia had always been singled out for special hatred.

Despite the determined effort made by White society to eradicate the Mi'kmaq language, it is still alive and healthy today throughout most of Cape Breton, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island; and surprisingly, almost half of the Mi'kmaq on mainland Nova Scotia can still converse in their mother tongue-another example of the Mi'kmaq's dauntless spirit.

In 1892, trying to come up with a way to educate Maliseet and Mi'kmaq children, the Department toyed with the idea of building a residential school farm in Nova Scotia. However, probably because education was not much of a priority in the Department's estimation, the decision to actually build such a school in Canada's Maritime Provinces was not made until 1927. It was opened off-Reserve in the village of Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia, in 1930.

The teaching staff were recruited according to the section of the Indian Act that mandated that teachers be of the same faith as the children they were teaching. As most of the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet were Catholic, the teachers were Roman Catholic nuns and the principal a priest. The curriculum was the same as that prescribed by the Nova Scotia Department of Education for the provincial school system except for the courses in religion and in how to be ashamed of being an Indian. Children were taught about all the advantages of White life and all the evils of First Nations' isolation, language and culture.

Besides delivering second-rate education, these institutions were also used by Indian Affairs for many other purposes, enforcement, punishment and terrorism, to name a few. Because of their "wards of the Crown" status, no possibility for legal redress was available to Registered Indians victimized at these facilities. So, when reading the following material, please bear in mind that the fights waged by parents and other relatives in trying to access and protect their children incarcerated in the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School were taken on without access to the laws that protected White Canadians from being victimized by the heavy hand of the state. Thus, many suffered greatly.

I'll start this short overview of the Shubenacadie residential school by relating the less than fond experiences of distinguished former resident Elsie Basque, née Charles. Elsie was born in 1916, to Margaret Labrador and Joe Charles, at Hectanooga, Digby County, Nova Scotia. She has many fond memories of her early years, but they were not without tears and tragedy. By the end of her third year, Joe was hospitalized with tuberculosis and her mother had left the family permanently. But things got better. In 1922 Joe's TB stabilized and life at home in Hectanooga returned to a peaceful existence.

Elsie remembers "papa" as being her most important childhood influence. His advise that "To be somebody, one needs a good education" is still fondly recalled. In tune with his belief, Joe enroled her in the old one-room school in Hectanooga where she completed grade 7. Then her life was drastically changed by the information contained in an article her father had read in a 1929 edition of the Halifax Chronicle which touted the new horizons being opened up for the Mi'kmaq by the opening of the residential school. Believing the school was a golden opportunity to secure his daughter's education, Joe enroled her.

This is Elsie's assessment of the two years she spent there:

"I've always regarded these years as time wasted.... I was in the 8th grade when I arrived at the school in February 1930 and in the 8th grade when I left in 1932. What had I learned in those 28 months? How to darn a sock, sew a straight seam on the sewing machine, and how to scrub clothes on a washboard. Educationally, how to parse and analyze a sentence.

Volumes have been written about the school. Its total disastrous effect upon the Mi'kmaq/Maliseet Nations will never be known. Generations later, the scars remain. It was not an education institution as we define education. Older children, boys and girls were taken out of the classroom to do chores-milk cows, clean the barn, plant and harvest, etc. The girls were ordered to launder clothes, make uniforms, scrub the floors and so on."

After this disappointment, Elsie, who is fluent in French, returned to Clare and enroled at Meteghan's Sacred Heart Academy, where she graduated with a high school diploma in 1936. She then entered classes at the Provincial Normal College in Truro and was awarded a teacher's certificate in 1937. Thus she became the first licensed Mi'kmaq teacher in Nova Scotia. Notably, she was well treated at the college by peers and administration. The students elected her class president and she describes her time there as a "fun year."

The year was capped by a rare honour. The principal of the college, Dr. Davis, permitted very exceptional students to use his name as a reference. In 1937 only three were permitted to do so, and Elsie was one of them! With teaching license in hand, she applied by mail in mid-1937 to the Inverness County School Inspector for a teaching job at Mabou Ridge. This is how she describes her first face-to-face meeting with the inspector-it was also her first experience with overt racism:

"On our short drive to his home in Port Hastings, he advised that it would be best for me to turn around and go home. He was certain that the good people of Mabou Ridge would never accept a Micmac to teach their children. After much discussion it was agreed that I could at least try. The next day, teaching duties were undertaken without opposition from the community, the year passed without incident." [In the mid-1980s Elsie returned to Mabou Ridge and was given a warm welcome.]

If Elsie had applied in person she would not have got the job. Incidents such as this prove that officialdom was at the forefront of racial discrimination in Nova Scotia.

In view of the racism afoot in this province at the time, I had often wondered where Elsie had got the courage to attend a White institution and become a teacher. Then she gave me an explanation that reflected Maritime history. Raised among the Acadian people, Elsie had not experienced the self-confidence-destroying racial discrimination in youth that was suffered by most of Nova Scotia's Mi'kmaq:

"I grew up in the area of Nova Scotia known as Clare ... an area where one is accepted for who and what one is, not on ethnic background. The bonds of friendship and understanding that began with Chief Membertou, Champlain, De Monts, Poutrincourt, have never faltered. Their legacy lives on."

In 1992, Marilyn Millward wrote an article about the residential school entitled "Clean Behind the Ears?" These are some shocking excerpts from it:

"Many of the students who attended the old Shubenacadie Indian Residential School carry with them the scars of that experience. But they were not the only ones to suffer. A look at surviving records reveals the anguish many parents endured, and shows the determination to speak and be heard that was their reaction to the way the educational and governmental bureaucracy dealt with them and their children.

The Indian Residential School at Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia, operated between February 1930 and June 1967. It was intended to accommodate Micmac (and Maliseet) children who were deemed to be "underprivileged," defined by the Federal Department of Indian Affairs as orphaned, neglected, or living too distant to permit attendance at any day school. While children who were orphaned or remote from schools could be easily identified, it was more difficult to interpret the term "neglected." This was a matter to be determined by the local Indian Agent.

Here, the Department intended to "consolidate Indian educational work in the Maritimes" and planned to "mould the lives of the young Aborigines and aid them in their search towards the goal of complete Canadian Citizenship." Duncan C. Scott, then Deputy Superintendent General of the Department of Indian Affairs, told the Halifax-Chronicle that their object and desire in establishing the new school was that its graduates should become self-supporting and "not return to their old environment and habits."

Millward states that parental permission was necessary for admission. Although she later qualifies this statement, it isn't true. She may not have been aware that, because we were "wards of the Crown," the law as it then stood gave control of such things to Indian Affairs. The parental permission portions of the forms for admission to the school were simply window dressing. The Indian Agents did not legally need our permission to do anything they wanted to do with us, and they used these powers at will.

Ms. Millward substantiates this fact when describing how a Mi'kmaq parent tried to keep a child home:

"A mother wanted to keep her children home after their vacation, and believed that only a note to her agent to that effect was necessary. When she learned "it wasn't her decision to make," she had a justice of the peace write to the Department on her behalf. His help consisted of a note saying that this mother "says she 'loves' her children"-the word "loves" was belittled and negated by quotation marks. The agent wrote that she wanted them home only to take care of the house and their younger siblings, and so her request was apparently unsuccessful."

The Department's control over the lives of children and parents was all-encompassing. Ms. Millward reports of vacations:

"Perhaps because of the difficulty in having some of the children returned to the school after summer vacations, holidays at home were not allowed for any children during Christmas. Although specific reasons for this policy are not clear from the existing records, they are implied in a 1938 letter from the Department to an agent in the Annapolis Valley: "For many reasons which will no doubt suggest themselves to you, the Department does not allow holidays at Christmas, and I might say further that no valid reason has yet been given to us why holidays should be allowed at that period of the year. There is no question that the children attending the Shubenacadie Residential School receive every possible care and attention, and in addition at Christmas time there are always special festivities which the children enjoy.

In 1939, the parents at the Cambridge Reserve in Nova Scotia were determined to have their children home for Christmas, but the agent refused their request and advised them of the Department's rules. Reporting on the matter to the Department, he wrote: "These people went so far as to have a man go to the school for their children, [but] they did not get the children. The Principal would not let them take them."

When one of these parents then sent her request to the Department herself, the agent reported: "She thought by writing she would be able to get her children home for Christmas. These people think that they can have their own way and would like to do so and when they find out they cannot they get mad."......

For the full story please go to Chapter 13, Twentieth-Century Racism and Centralization, of We Were Not the Savages.

By Daniel N. Paul, January 3, 2008

Nora was born, September 22, 1935, to the late Mary (Cope) and Michael Bernard. Her place of birth was the Mi’kmaq First Nation Community of Millbrook. She is survived by her six children, thirteen grandchildren, six great-grandchildren, and four of her seven siblings, an uncle, and hundreds of other relatives, who are so numerous that at the time of her untimely passing, December 27, 2007, she had not met a great many of them.

The large extended family into which Nora was born includes me and my siblings. Her mother Mary and ours, Sarah, were double first cousins. Mary’s parents were brother and sister to my mother’s parents. Our ancestry on the Cope side can be traced back to Sipekne’katik District Chief Sachem Jean Baptiste Cope, who negotiated with the British the Treaty of 1752, and beyond.

Nora and I first became acquainted when we were very young, so young that I don’t have any recollection of the first time. But, I do recollect that she had a great smile that she greeted me with whenever we met. The last time I enjoyed it, a few pleasantries, and a hug, was at the Millbrook Elders dinner on December 12, 2007. It will be a fond memory for me for the rest of my time on Mother Earth.

During our early years, our families, as well as most other Mi’kmaq families, shared a dreaded thing in common, dire poverty. On many days meals were missed, our cloths were second-hand, and our homes were little better than decrepit shacks. Luxury items, such as choice meat cuts, were few and far between. However, even in such dire conditions, love and laughter were not absent in our lives.

Another thing our families shared in common was family members incarcerated in the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School. My two older brothers, Bob and John, were incarcerated there in the late1930s, and during their stay were witness to many of the horrors that occurred within its confines during that period. Their description of them to us were so scary that we were in dread of ever being incarcerated in the place. Thankfully, I never had the personal experience of residing within its walls.

However, Nora and her siblings were not so lucky, they were incarcerated there, which experience later inspired her to take on the powers that be and demand redress. When she got her project for justice underway in the 1980s, she labored at it with tenacious dedication, nothing could derail her from realizing her dream. The formation of the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School Association was soon a reality.

In 1996, John McKiggan, a lawyer that Nora finally found who would take on their case, filed a class action lawsuit on Nora’s behalf. It inspired similar suits across Canada, which eventually led to the 2006 class action settlement of approximately five billion dollars, the largest in Canadian history. McKiggan says of Nora: “"I firmly believe that if it wasn’t for Nora’s efforts, and other survivors like her across Canada, this national settlement never would have happened."

Hats off to Nora, who had the courage to take on the impossible and stay with it until justice was found. I do hope that her efforts will inspire more and more First Nations Peoples across the Americas to say “no more, we want and will fight for justice for the injustices that we and our ancestors suffered at the hands of Caucasian societies now!”

May the Great Spirit grant Nora a happy place in the Land of Souls for eternity!

Nora was named Posthumous to the Order of Nova Scotia on September 4, 2008. Her name will be invested into the Order on October 8, 2008.

Province honours slain native activist, Bernard, 5 others join Order of N.S.

By AMY SMITH Staff Reporter, Oct 9, 2008

NATIVE RIGHTS activist Nora Bernard would have been proud and a little bit shy about receiving the Order of Nova Scotia Wednesday, said the man who nominated her for the honour.

Dan Paul, the slain woman’s second cousin, said Ms. Bernard’s fight for justice for residential school survivors truly deserves recognition.

Ms. Bernard was the driving force behind the largest class-action suit in the country, which represented 79,000 survivors, and in 2007 the federal government settled the suit for more than $5 billion.

"When you are looking at Nora Bernard and what she did, I think it’s a pinnacle in Canadian history that somebody had the courage to face down the powers that be across this country," Mr. Paul, a historian who received the Order of Nova Scotia in 2002, said after the ceremony at Province House that honoured Ms. Bernard and five other Nova Scotians.

"Let’s put it this way: The opposition to what she accomplished was formidable. When you are taking on several levels of government, the churches and what have you across the country and you overcome, maybe there’s not an honour high enough that can be awarded to such a person."

Ms. Bernard, 72, was found stabbed and beaten in her Truro home last December. Her grandson James Douglas Gloade, 25, of Millbrook First Nation pleaded guilty to manslaughter.

During Wednesday’s investiture ceremony at the legislature’s Red Room, Ms. Bernard’s son Jason accepted the honour on her behalf.

Ms. Bernard was definitely with her son in spirit, her sister Linda Maloney said.

"She would have been very proud to walk up there and receive this honourable award," Ms. Maloney said, her voice breaking. "And she would have displayed it proudly."

Sister Dorothy Moore, chairwoman of the Order of Nova Scotia Advisory Council, described Ms. Bernard as "a beautiful, thoughtful person who cared deeply for her friends, family and community."

"I think Nora left a legacy," Sister Moore told reporters. "She died but she didn’t die. She continues to live."......

asmith@herald.ca

Text of Harper's residential schools apology

THE CANADIAN PRESS

June 11, 2008 at 5:23 PM EDT

OTTAWA — Text of Prime Minister Stephen Harper's residential schools apology Wednesday:

Mr. Speaker, I stand before you today to offer an apology to former students of Indian residential schools.

The treatment of children in Indian residential schools is a sad chapter in our history.

In the 1870's, the federal government, partly in order to meet its obligation to educate aboriginal children, began to play a role in the development and administration of these schools.

Two primary objectives of the residential schools system were to remove and isolate children from the influence of their homes, families, traditions and cultures, and to assimilate them into the dominant culture.

These objectives were based on the assumption aboriginal cultures and spiritual beliefs were inferior and unequal. indeed, some sought, as it was infamously said, “to kill the Indian in the child.” Today, we recognize that this policy of assimilation was wrong, has caused great harm, and has no place in our country.

Most schools were operated as ‘joint ventures' with Anglican, catholic, Presbyterian or united churches.

The government of Canada built an educational system in which very young children were often forcibly removed from their homes, often taken far from their communities.

Many were inadequately fed, clothed and housed. all were deprived of the care and nurturing of their parents, grandparents and communities.

First Nations, Inuit and Metis languages and cultural practices were prohibited in these schools.

Tragically, some of these children died while attending residential schools and others never returned home.

The government now recognizes that the consequences of the Indian residential schools policy were profoundly negative and that this policy has had a lasting and damaging impact on aboriginal culture, heritage and language.

While some former students have spoken positively about their experiences at residential schools – these stories are far overshadowed by tragic accounts of the emotional, physical and sexual abuse and neglect of helpless children and their separation from powerless families and communities.

The legacy of Indian residential schools has contributed to social problems that continue to exist in many communities today.

It has taken extraordinary courage for the thousands of survivors that have come forward to speak publicly about the abuse they suffered.

It is a testament to their resilience as individuals and to the strength of their cultures. regrettably, many former students are not with us today and died never having received a full apology from the government of Canada.

The government recognizes that the absence of an apology has been an impediment to healing and reconciliation.

Therefore, on behalf of the government of Canada and all Canadians, I stand before you, in this chamber so central to our life as a country, to apologize to aboriginal peoples for Canada's role in the Indian residential schools system.

To the approximately 80,000 living former students, and all family members and communities, the government of Canada now recognizes that it was wrong to forcibly remove children from their homes and we apologize for having done this.

We now recognize that it was wrong to separate children from rich and vibrant cultures and traditions, that it created a void in many lives and communities, and we apologize for having done this.

We now recognize that, in separating children from their families, we undermined the ability of many to adequately parent their own children and sowed the seeds for generations to follow and we apologize for having done this.

We now recognize that, far too often, these institutions gave rise to abuse or neglect and were inadequately controlled, and we apologize for failing to protect you.

Not only did you suffer these abuses as children, but as you became parents, you were powerless to protect your own children from suffering the same experience, and for this we are sorry.

The burden of this experience has been on your shoulders for far too long. the burden is properly ours as a government, and as a country.

There is no place in Canada for the attitudes that inspired the indian residential schools system to ever again prevail.

You have been working on recovering from this experience for a long time and in a very real sense, we are now joining you on this journey.

The government of Canada sincerely apologizes and asks the forgiveness of the aboriginal peoples of this country for failing them so profoundly. we are sorry.

In moving towards healing, reconciliation and resolution of the sad legacy of Indian residential schools, implementation of the Indian residential schools settlement agreement began on September 19, 2007.

Years of work by survivors, communities, and aboriginal organizations culminated in an agreement that gives us a new beginning and an opportunity to move forward together in partnership.

A cornerstone of the settlement agreement is the Indian residential schools truth and reconciliation commission.

This commission presents a unique opportunity to educate all Canadians on the Indian residential schools system.

It will be a positive step in forging a new relationship between aboriginal peoples and other Canadians, a relationship based on the knowledge of our shared history, a respect for each other and a desire to move forward together with a renewed understanding that strong families, strong communities and vibrant cultures and traditions will contribute to a stronger Canada for all of us.

God bless all of you and God bless our land.

OBSERVATION

Let's say I'm somewhat encouraged, not overwhelmed, by Mr. Harper's apology - it touches the tip of the iceberg. I will congratulate him on this, he has gone further than any Prime Minister has gone to-date in acknowledging Canada's inglorious past mistreatment of First Nation Peoples, but, he didn't go overboard.

Today, I would encourage National Chief Phil Fontaine, and others, to keep in mind that our First Nations are owed an apology for a long list of horrors perpetuated against our Peoples by Canadian and British colonial governments. A few examples, the extermination of the Beothuk, the use of scalp proclamations to try to exterminate the Mi'kmaq, medical experimentation, Indian Act sections that barred us from pool rooms, from hiring lawyers to fight our claims, centralization in the Maritimes, economic exclusion, etc., etc., the list is extensive.

When the day comes that a Canadian Prime Minister gets up in the House of Commons and make a full unequivocal apology for all the wrongs we and our ancestors suffered, it will be the day that we can fully celebrate.

Daniel N. Paul, June 12, 2008

Please click the following to read a 1999 newspaper column I wrote about Canada's efforts to use adoptions and the schools as tools to exterminate First Nations Cultures. It's entitled "All-consuming desire to kill First Nations' cultures. http://www.danielnpaul.com/Col/1999/All-ConsumingDesireToKillFirstNationCultures.html

For an overview of American Indian Residential Schools Please Click: http://www.danielnpaul.com/CarlisleIndianSchool.html

The Fallen Feather Website has some very interesting films about the Schools: http://www.fallenfeatherproductions.com/

Winnipeg Free Press - November 6, 2009

Long buried truths emerging

Unmarked graves of aboriginal people who died in government care a disgrace

By: Catherine Mitchell

Among the many euphemisms we have constructed to describe dying is the idea that in death we lose a loved one or a part of ourselves. It is an apt description of the pain that takes hold -- a life is "lost" to us.Imagine the anguish if it were literally true, if a loved one vanishes without a trace. There is no rite of passage, and no physical place to unload the sorrow.

So the anguish carries on.

In Canada, there are hundreds of graves, unmarked and overgrown, holding the remains of thousands of "lost" souls. The grave sites are the resting places of so many aboriginal people who died after being forcibly taken from their families by government policy, to residential schools for assimilation or to urban hospitals when disease overwhelmed rudimentary medical care in Canada's rural or remote areas.

Many, and perhaps most, of the burial sites are nearly obliterated by the passage of time and bereft of markers. They sit like pockmarks on Canada's conscience.

The story of the abuse, neglect and indignity inflicted by government policy is erupting finally into the national consciousness.

My colleague Jen Skerritt did a terrific job in Wednesday's paper documenting the pain of First Nations families who saw loved ones lifted out of their communities for treatment of tuberculosis in Manitoba sanitoriums.

I was struck by the similarities of that story to the tales I heard last spring from residents of the Eastern Arctic communities of Rankin Inlet and Arviat whose loved ones, killed in a Northern Manitoba plane crash in 1949, were buried in a mass, unmarked grave at the nearby Norway House reserve. The seven Inuit passengers, on their way to polio treatment in Winnipeg, were the only ones of the 20 Canadians aboard the plane whose bodies were not transported back to their home towns for burial. All others were non-aboriginal.

Canada was quick to assert its authority and responsibilty to "rescue" the sick, but its humanity had limits. In death, a body became an inconvenience.

How many died in government "care" remains to be documented -- the story yet untold from Canada's sorry history of inhumane treatment of indigenous people, a local historian told me. They were buried in fields adjoining schools, or municipal cemeteries. Most of those schools have been torn down and the plots forgotten and grown over.

One cemetery used by the United Church residential school in Brandon is in private hands now, part of a trailer park, a private researcher hired by the church told me.

Government policy deemed as unacceptable the expense of transporting bodies back to their families.

It has yet to be documented exactly how many children, for example, died while attending 145 residential schools across Canada (but mostly in the West) from the late 1800s until the late 1960s when most were closed.

Justice Murray Sinclair, in a recent address at the University of Winnipeg, gave a compelling description of how impotent the parents and community leaders were when their children were forced into Christian schools for assimilation starting in 1870s, long before education became compulsory in Canada. Parents had been stripped by federal law of the right to protest or resort to the court, noted Sinclair, now the chairman of the national Indian Residential School Truth and Reconciliation Commission. First Nations parents could be forbidden to visit their children, requiring a pass to leave the reserve from the very Indian agents that gathered and transported children to the schools.

When the kids died, they were buried by the schools without notice to the families left to wonder why they never came home.

But the dead often don't stay down and people are starting to ask questions. Skeletons are beginning to poke up through the soil of their ignominious resting grounds. Graves, forgotten and unrecorded, are being bulldozed for development and the truth is emerging. The protests and outrage, ever legitimate but today abundantly legal, of the people are being heard.

The clamour to find the graves, to identify the remains and repatriate them to their family lands is growing. I encourage all Canadians to join in the campaign for a reconciliation past due.

It will be tough because little care, not surprisingly, was paid to the details of burials, plots and cemeteries. Records, where they existed, were lost and the unmarked graves have been reclaimed by the elements. Forgotten, except by some loved ones who spent a lifetime wondering.

The search for the remains is part of the debt Canada owes to make amends for a history of institutionalized abuse against indigenous people, to set right the denial of basic decency to those often regarded as something less civilized.

John Duncan, Canada’s Minister of Indian Affairs, recently stated that cultural genocide was never attempted in Canada, my response:

In one of his so-called “Indian Poems”, white supremacist Duncan Campbell Scott , Deputy Minister of Canada’s Indian Affairs, wrote:

She stands full-throated and with careless pose,

And closer in the shawl about her breast,

The Canadian Government’s denial that Cultural Genocide and out and out Genocide were never attempted by British colonial and Canadian governments in what is today Canada is ludicrous, preposterous, and delusional! The extinction of the Beothuk and three British proclamations for Maliseet and Mi’kmaq scalps, plus other horrors under British colonial rule that are too numerous to mention here, if not Genocidal attempts, what were they, warped insane attempts to assure survival? Then, under Canadian rule, malnutrition rations, minimal health care, Indian residential and Indian day schools that were set up specifically for taking the Indian out of the Indian, other government Indian Affairs policies that were also enacted for the express purpose of exterminating First Nation Cultures, etc., if these were not an all out attempt to commit Cultural Genocide what were they, more warped insane attempts to assure survival? As one who is old enough to remember the humiliation of being degraded by overt white supremacist racism in my youth, my advice for elected and non-elected Canadian Indian Affairs officials is to take your heads out of the sand and have a reality check! They could begin to acquire enlightenment by reading the following short story.

Prime Minister Harper’s Indian Residential School apology draws attention to Duncan Scott Campbell, the Deputy Minister in charge of Indian Affairs Branch from 1913 to 1932. Campbell described the residential school program as an attempt “to kill the Indian in the child.”

Mortality rates at the residential schools soared during Campbell’s reign. Many students contracted tuberculosis and were forced to sit through classes as their health deteriorated, ensuring that healthy students would be exposed to the virus.

Scott addressed the issue in 1924 in one of the most chilling statements in Canadian history.

“It is readily acknowledged that Indian children lose their natural resistance to illness by habituating so closely in the residential schools and that they die at a much higher rate than in their villages. But this does not justify a change in the policy of this Department which is geared towards a final solution of our Indian Problem.”

About Duncan Campbell Scott

As the bureaucratic head of Indian Affairs Branch from 1913 to 1932, Duncan Campbell Scott had among his responsibilities the direction and management of Canada’s Indian residential school system.

The Encyclopedia Britannica reports that he “allowed school staff to use a variety of inhumane punishments to implement and enforce the assimilation of these children.”

Scott left a record of his thoughts during his 20 year command of the Department of Indian Affairs. His duplicitous writing reveals a carefully crafted policy of cultural genocide. It is chilling to realize that Campbell wrote the following policy statements in the 1920’s.

“The policy of the Dominion (of Canada) has always been to protect Indians, to guard the identity as a race and at the same time to apply methods which will destroy that identity and lead eventually to their disappearance as a separate division of the population.”

Reference: From a work of literary criticism produced as a Masters thesis by Nancy Chater at OISE in Toronto in 1999.

Library of Canada 0-612-45483-5

TECHNOLOGIES OF REMEMBRANCE:

Chater pulled the quote from a book titled The Age of Light, Soup and Water: Moral Reform in English Canada 1885 - 1925 by . Valverde is a criminology prof at University of Toronto Mariana Valverde Also Wikipedia Mariana Valverde

Scott’s role as Canada’s top Indian Affairs bureaucrat enabled him to travel on Indian territory at tax payer expense and write pretentious lamentations about the people he was determined to destroy.

Thanks to Michael Jack Lawlor for his input.

Daniel N. Paul, November 26, 2011

On December 6, 2011, I received a memo from an Acadien Friend, Cyrille LeBlanc, commenting about the renaming of the Cornwallis school, and another issue, the Nova Scotia education Department’s past policy of forbidding the use of a person’s non-English mother tongue on the Province’s school grounds. It’s a most interesting comparison of the cultural abuses suffered by both Acadiens and First Nation’s children.

Daniel,

That's great regarding the (renaming of the Cornwallis School). I heard that on the news yesterday and thought of you.

On another issue. The sad story of the residential schools which is troubling. Acadian can relate to this story - minus the sexual abuse. That part was the domain of our Acadian priests. That didn't happen to me, but many of my age, including some close friends, were victims.

There were schools in Acadian villages of Richmond County and Yarmouth County where the Acadian Francophone students were punished for speaking French. Fifty one years ago this year the Pinkney's Point school in Yarmouth County was closed and the students (all Acadians) were sent to the Arcadia School in an Anglophone community. They were punished for speaking French on the school grounds. At recess time they would post a guard to be on the look out for teachers to tell their friends to stop speaking French.

Some Pinkney's Point parents stopped speaking French at home to their children so they would not get punished at school. The French language is now lost among the young of this Acadian community. Pinkney's Point was originally established by New England Planters who came to Yarmouth County to replace the Acadians who were deported. An Acadian Surette family from Wedgeport moved to Pinkney's Point. Gradually other Acadians moved in. The descendants of the Planters moved out.

Spinghaven, where most Acadians are Métis, in Yarmouth County there were a few Anglophones who ran things such as the school. At the Spinghaven School the Acadians were also punished for speaking French. Acadian families stopped speaking French in the home. However I don't know anyone who does not speak French.

In Richmond County catholic nuns of Scottish descent would punish Acadian Francophone students if they spoke French on the school grounds. Today most residents of Richmond County are of Acadian descent. But only a minority speak French and they live in the Petit-de-Grat area.

These issues are being discussed today because of the Electoral Boundaries Legislative Committee going around the province.

Cyrille LeBlanc, Wedgeport NS

At least 3,000 died in residential schools, research shows

Dormitories for aboriginal children in disgraced system were disease 'breeding grounds'

The Canadian Press

Posted: Feb 18, 2013 12:18 PM ET

Last Updated: Feb 18, 2013 12:32 PM ET

At least 3,000 children, including four under the age of 10 found huddled together in frozen embrace, are now known to have died while they were attending Canada's aboriginal residential schools, according to new unpublished research.

While deaths have long been documented as part of the disgraced residential school system, the findings are the result of the first systematic search of government, school and other records.

"These are actual confirmed numbers," Alex Maass, research manager with the Missing Children Project, told The Canadian Press from Vancouver.

"All of them have primary documentation that indicates that there's been a death, when it occurred, what the circumstances were."

The number could rise further as more documents — especially from government archives — come to light.

The largest single killer, by far, was disease.

'The schools were a particular breeding ground for [tuberculosis]. Dormitories were incubation wards.' Research manager Alex Maass

For decades starting in about 1910, tuberculosis was a consistent killer — in part because of widespread ignorance over how diseases were spread.

"The schools were a particular breeding ground for [tuberculosis]," Maass said. "Dormitories were incubation wards."

The Spanish flu epidemic in 1918-1919 also took a devastating toll on students — and in some cases staff. For example, in one grim three-month period, the disease killed 20 children at a residential school in Spanish, Ont., the records show.

While a statistical analysis has yet to be done, the records examined over the past few years also show children also died of malnutrition or accidents. Schools consistently burned down, killing students and staff. Drownings or exposure were another cause.

In all, about 150,000 First Nations children went through the church-run residential school system, which ran from the 1870s until the 1990s. In many cases, native kids were forced to attend under a deliberate federal policy of "civilizing" Aboriginal Peoples.

Many students were physically, mentally and sexually abused. Some committed suicide. Some died fleeing their schools.

One heart-breaking incident that drew rare media attention at the time involved the deaths of four boys — two aged 8 and two aged 9 — in early January 1937.

A Canadian Press report from Vanderhoof, B.C., describes how the four bodies were found frozen together in slush ice on Fraser Lake, barely a kilometre from home.

The "capless and lightly clad" boys had left an Indian school on the south end of the lake "apparently intent on trekking home to the Nautley Reserve," the article states.

A coroner's inquest later recommended "excessive corporal discipline" of students be "limited."

The records reveal the number of deaths only fell off dramatically after the 1950s, although some fatalities occurred into the 1970s.

"The question I ask myself is: Would I send my child to a private school where there were even a couple of deaths the previous year without looking at it a little bit more closely?" Maass said.

"One wouldn't expect any death rates in private residential schools."

In fact, Maass said, student deaths were so much part of the system, architectural plans for many schools included cemeteries that were laid out in advance of the building.

Maass, who has a background in archeology, said researchers had identified 50 burial sites as part of the project.

About 500 of the victims remain nameless. Documentation of their deaths was contained in Department of Indian Affairs year-end reports based on information from school principals.

The annual death reports were consistently done until 1917, when they abruptly stopped.

"It was obviously a policy not to report them," Maass said.

In the 1990s, thousands of victims sued the Canadian government and the churches that ran the 140 schools. A $1.9-billion settlement of the lawsuit in 2007 prompted an apology from Prime Minister Stephen Harper, and the creation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

The research — carried out under the auspices of the commission — has involved combing through more than one million government and other records, including nuns' journal entries.

The longer-term goal is to make the information available at a national research centre.

“It is our history, our shaping of the new world,” Milloy writes. For white writers to treat residential schools as solely someone else’s story is to miss the chance to learn about ourselves, to live in a society better able “to deal justly with the Aboriginal people of this land.” We tried to erase hundreds of cultures across the land. To open ourselves to that history is to feel crippling guilt or daunting responsibility. Maybe that’s why we avoid it, or why we treat residential school as if it’s only in the past, ignoring its living legacy and the ongoing divide between Euro-Canadian and Aboriginal cultures.

That state of denial allows things to continue as they always have, with settler Canadians taking from Aboriginal peoples instead of living in partnership. I am writing this book in the hopes of better understanding the crimes European-Canadians committed and are committing against the First Nations of the Maritime region, and to push myself to be a better ally. As educator Paulo Freire one wrote, “Washing one’s hands of the conflict between the powerful and the powerless means to side with the powerful, not to be neutral.” The only way I can avoid participating in oppression is by participating in the struggle against it.

To do this, I need to move past learning and be a witness, telling others what I’ve learned. Despite all the media coverage, non-Aboriginal people still don’t know about residential schools. In 2008, the research firm Environics found only a third of Canadians were “familiar with the issue of native people and residential schools.” And only five percent said they were “very familiar” with these issues. More than a third had heard about physical and sexual abuse, but just twenty percent realized that children had been separated from their families, and only ten percent knew they weren’t allowed to speak their mother tongues.

“We still know very little” As Paulette Regan wrote, there is no Indian Problem. There never was. What we have here is a settler problem – a deep-seeded belief that one culture is better than the other. Only from the place of cultural arrogance can we proclaim solutions for other people’s problems – problems defined and created by the same arrogance. Too often we hear, and tolerate, criticisms of the Mi’kmaq for failing to “get with the times” or “stop whining about the past.” In other words, assimilate into our ways; forget your history, tradition, and culture. Give up who you are and become us instead. The inherent assumption is that we are better.

And yet, by the time Knockwood came along, Euro-Canadians saw the Mi’kmaq as an inferior people. A 1947 Bachelor of Education thesis for Mount Allison University called “Indian Education in Nova Scotia” begins: “Determining the relationship between the Indians and the whites became an immediate problem with which the latter, because of their superiority, were forced to contend.”

Early Europeans were amazed by the kindness Mi’kmaq showed children. They wrote much of their incredible freedom and egalitarianism. The explorers were perplexed that people lived more or less equally, with leaders taking on more power but also far more responsibility. The land was absent of dictators. Leaders seemed to have the genuine respect of their people. Yet there was complexity in their governance, which had three levels – local bands, district leadership and band council. Modern democratic systems were modeled after Indigenous systems.

CBC News · Posted: May 30, 2021

British Columbia, Canada

Indigenous leaders, experts call for protection of sites of former residential schools

Social Sharing

Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation said remains of 215 children were found at unmarked site in Kamloops, B.C.

About 100 people gathered Saturday night at the site of the former Kamloops residential school, where the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation said the remains of 215 children were discovered last week. (Briar Stewart/CBC)

WARNING: This story contains details some readers may find distressing.

Indigenous leaders and experts in British Columbia are calling for the protection of sites of former residential schools after the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation said the remains of 215 children were found at one such site in Kamloops, B.C.

They warn that this represents just a small portion of the thousands who died while the schools were in operation.

Linc Kesler, an associate professor at the University of British Columbia's Institute for Critical Indigenous Studies, said it's only a matter of time before the same type of technology used by the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation reveals more physical evidence of the horrors of residential schools across Canada.

"It's absolutely not an isolated incident," Kesler said.

On Thursday, Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc said preliminary findings from a ground-penetrating radar survey uncovered the remains.

Work underway for forensic experts to identify, repatriate children's remains from B.C. residential school

Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, director of the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre at the University of British Columbia, agreed that the residential school sites should be protected.

"We need to make sure they are controlled and protected so full investigations can be done," Turpel-Lafond said.

'We're all grieving'

B.C. Assembly of First Nations Regional Chief Terry Teegee said he too would like the sites to be protected — but bureaucratic red tape has added layers of complication.

Teegee said Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc started the process of finding the remains 20 years ago.

He said it would take all levels of government to come together in order to remove barriers and provide the resources needed to identify and commemorate all the children who went missing while at residential schools.

"These children had a home. These children were loved by somebody," he said.

B.C. Assembly of First Nations Regional Chief Terry Teegee said the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation started the process of finding the remains 20 years ago. (Rafferty Baker/CBC)

More than 100 people gathered in front of a sacred fire at the site of the Kamloops residential school Saturday evening, standing shoulder to shoulder to grieve.

Marie Narcisse was part of the crowd on Saturday. She attended the school as a child, as did her parents.

"So many times the oral stories of this place and many other places were told and it seemed as though nobody believed anybody," she said.

Marie Narcisse, left, and her sister were among the crowd at the site of the Kamloops residential school on Saturday evening. (Briar Stewart/CBC)

On Sunday, Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc Kukpi7 (Chief) Rosanne Casimir said there will be a debrief with the nation's membership this week, adding that other chiefs across Canada are having similar conversations with their communities as well.

"We're all grieving," Casimir said. "There's so many unanswered questions that our membership wants. The world wants to know."

Casimir said the discovery adds a very dark chapter to Canadian history and the state-funded residential school system.

School closed in 1978

Narcisse and her younger sister lingered in front of the memorial at the site of the residential school for more than an hour.

In front of the school is a memorial with dozens of names etched on a plaque. At the base of it people have left flowers and notes. On top rests a tiny pair of shoes.

The former Kamloops Indian Residential School. Indigenous leaders and experts are calling for the protection of unmarked burial sites to allow for further investigations. (Andrew Snucins/The Canadian Press)

Historical records had indicated that 50 children died at the school, but this new discovery shows that estimate was likely dramatically low.

The Kamloops Indian Residential School was in operation from 1890 to 1969, when the federal government took over administration from the Catholic Church to operate it as a residence for a day school, until closing in 1978.

Flags on federal buildings lowered in memory of Kamloops residential school victims

Searching for records

Enrolment at the school peaked in the early 1950s at 500, according to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR). Those children would have come from First Nations communities across B.C. and beyond.

Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc said they are working with the BC Coroners Service, contacting the students' home communities, protecting the remains and working with museums to find records of these deaths.

Communities across Canada have been mourning and honouring 215 residential school children since last Thursday, when Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation said their remains were found at the site of a former residential school in Kamloops, B.C., using ground-penetrating radar. Today, people pay their respects at a growing memorial in Vancouver. (Ben Nelms/CBC)

Casimir previously told CBC News the missing children were undocumented deaths, some of them as young as three years old.

She said the findings are "preliminary" and a report will be provided by a specialist next month.

Teachers in B.C. to wear orange, hold special ceremonies over discovery of children's remains

Sask. First Nation set to examine residential school gravesite with radar this summer

Support is available for anyone affected by their experience at residential schools, and those who are triggered by the latest reports.

A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former students and those affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866-925-4419.

For an overview of American Indian Residential Schools Please Click: http://www.danielnpaul.com/CarlisleIndianSchool.html

Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Alleged Flogging of Indian Pupils at the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School, Clickhttps://activehistory.ca/2015/09/facing-down-r-b-bennett/

"Let all that is Indian within you Die" Shocking reading: http://www.twofrog.com/rezsch.html#statement >

Click to read about American Indian Genocide

This woman of a weird and waning race,

The tragic savage lurking in her face,

Where all her pagan passion burns and glows;

Her blood is mingled with her ancient foes,

And thrills with war and wildness in her veins;

Her rebel lips are dabbled with the stains

Of feuds and forays and her father’s woes.

The latest promise of her nation’s doom,

Paler than she her baby clings and lies,

The primal warrior gleaming from his eyes;

He sulks, and burdened with his infant gloom,

He draws his heavy brows and will not rest.

LITERARY CRITICISM AND DUNCAN CAMPBELL SCOTT'S "INDIAN POEMS"

Nancy Chater: A thesis submitted in confomity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, Department of

Curriculum, Teaching and Learning

Ontario Institute for Studies in Education

University of Toronto

Copyright by Nancy Chater, 1999