|

|

|

|

The manner in which information about the Northwest Resistence is dispersed and publicized by non-First Nation sources leads many people to believe that Louis Riel, a Métis, was the only individual hanged for daring to fight for freedom and justice for his people in what is now Canada’s prairie provinces. In fact, many from the Cree First Nation also joined the fight for freedom and justice for their People, and, for daring to do so eight were hung, and several, including Chief Poundmaker, were imprisoned.

Although Riel was allowed to appeal his death sentence it doesn’t appear that the Cree sentenced to death were given the opportunity to appeal. Riel was sentenced to death in July and executed in November four months later. The first Cree was sentenced to death on September 25, the rest in October, all were hung on November 27th. It probably was Quebec’s opposition to Riel’s hanging that gave him the four month’s grace. As white supremacist attitudes were still rampant at the time, especially among the Anglo population, I don’t imagine that Riel, a half-breed, was viewed as a cut above the Cree by the government of the day.

The persecution of the freedom fighters involved was a gross miscarriage of justice. It, and other incidents, and the inhuman way that First Nations People and Metis were treated by Canadian governments up until recent times - in 2010 discrimination and exclusion still prevail to an unacceptable level - is proof that Canada has as much to atone for, when it comes to the barbarities that governments perpetuated against our People in this country, as does the United States for what happened there. And, for that matter, the European Nations that invaded and colonized the Americas and displaced and decimated its rightful owners. However, when it comes to heartfelt and meaningful apologies from the governments of these Nations for the barbarities that the ancestors of their Caucasian citizens committed while "discovering" and settleing our lands the silence is deafening!

Daniel N. Paul, September 24, 2010

Quoted from a speech made by Sir John A. MacDonald, Prime Minister of Canada, in the Canadian House of Parliament, July 6, 1885, .

"...that we have been pampering and coaxing the Indians; that we must take a new course, we must vindicate the position of the white man, we must teach the Indians what law is..." "...along the whole frontier of the United States there has been war; millions have been expended there; their best and their bravest have fallen. I personally know General Custer, and admired the gallant soldier, the American hero; yet he went, and he fell with his band, and not a man was left to tell the tale -- they were all swept away..." The full speech can be read at:

Northwest Resistence

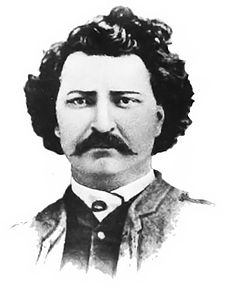

Louis Riel

Louis Riel, a leader of his people in their resistance against the Canadian government in the Canadian Northwest, is perhaps the most controversial figure in Canadian historiography. His life and deeds have spawned a massive and diverse literature.

He was born in the Red River Settlement (in what is now Manitoba) in 1844. A promising student, he was sent to Montreal to train for the priesthood, but he never graduated. An attempt at training as a lawyer ended similarly, and by 1868 Riel was back in the Red River area. Ambitious, well educated and bilingual, Riel quickly emerged as a leader among the Métis of the Red River. In 1869-1870 he headed a provisional government, which would eventually negotiate the Manitoba Act with the Canadian government. The Act established Manitoba as a province and provided some protection for French language rights.

Riel's leadership in the agitation, especially his decision to execute a Canadian named Thomas Scott, enraged anti-Catholic and anti-French sentiment in Ontario. Although chosen for a seat in the House of Commons on three occasions, he was unable to take his seat in the house. In 1875, Riel's role in the death of Scott resulted in his exile from Canada. These years in exile would include stays in two Quebec asylums and the growing belief in Riel that he had a religious mission to lead the Métis people of the Canadian northwest.

In 1884, while teaching in Montana at a Jesuit mission, Riel was asked by a delegation from the community of Métis from the south branch of the Saskatchewan river to present their grievances to the Canadian government. Despite Riel's assistance, the federal government ignored Métis concerns. By March of 1885, Métis patience was exhausted and a provisional government was declared.

Riel was the undisputed spiritual and political head of the short-lived 1885 Rebellion. He never carried arms and hindered the work of his military head, Gabriel Dumont. Riel was increasingly influenced by his belief that he was chosen to lead the Métis people. On May 15, shortly after the fall of Batoche, Riel surrendered to Canadian forces and was taken to Regina to stand trial for treason.

At his trial, Riel gave two long speeches which demonstrated his powerful rhetorical abilities. He personally rejected attempts by his defence counsel to prove he was not guilty by reason of insanity. On 1 August 1885, a jury of six English-speaking Protestants found Riel guilty but recommended mercy. Judge Hugh Richardson sentenced him to death. Attempted appeals were dismissed and a special re-examination of Riel's mental state by government appointed doctors found him sane. He was hanged in Regina on 16 November, 1885. His execution was widely opposed in Quebec and had lasting political ramifications.

Gabriel Dumont

Gabriel Dumont is best known as the man who led the small Métis military forces during the Northwest Resistance of 1885. He was born in the Red River area in 1837, the son of Isidore Dumont, a Métis hunter, and Louise Laframboise.

Although unable to read or write, Dumont could speak six languages and was highly adept at the essential skills of the plains: horseback riding and marksmanship. These abilities made Dumont a natural leader in the large annual Buffalo hunts that were an important part of Métis culture. At the age of fourteen Dumont received his initiation in plains warfare when he took part in a Métis skirmish with a large group of Sioux at the Grand Coteau of the Missouri River.

By the 1860s, Dumont was the leader of a group of hunters living in the Fort Carlton area. In 1872, he took advantage of the growing traffic on the Carlton trail and opened a ferry across the South Saskatchewan River and a small store upstream from Batoche. In 1873, his position as a leader was formalized when he was elected as president of the short-lived local government created by the Métis living on the south branch of the Saskatchewan.

His leadership role in the South Branch community continued. In 1877 and 1878, Dumont chaired meetings which drew up petitions to the federal government asking for representation on the Territorial Council, farming assistance, schools, land grants, and title to already occupied lands. Dumont was also a member of the delegation which convinced Louis Riel to return to Canada and plead the Métis case to the federal government.

When a provisional government was declared in 1885, Dumont was named "adjutant general of the Métis people." He proved himself an able commander and his tiny army experienced some success against government forces at Duck Lake and Fish Creek. The Canadian militia, however, proved too large and too well equipped for Dumont's army, which collapsed on 12 May 1885 after a four day battle near Batoche.

Dumont avoided capture by escaping to the United States where, in 1886, he accepted an offer to demonstrate his marksmanship by performing in Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show. After visits to Quebec (where he dictated his memoires in 1889) Dumont returned to his old homestead near Batoche. He lived there quietly until his death in 1906.

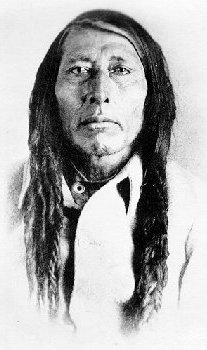

Chief Pitikwahanapiwiyin (Poundmaker)

Pitikwahanapiwiyin emerged as a political leader during the tumultuous years surrounding the extension of the treaty system and the influx of settlers into present-day Saskatchewan. Pitikwahanapiwiyin was recognized as a skilled orator and leader of his people by both Native and Non-native communities.

Born in about 1842 near Battleford in central Saskatchewan, Pitikwahanapiwiyin was the son of Sikakwayan, a Stoney shaman, and his Métis wife. Pitikwahanapiwiyin grew up with his Plains Cree relatives under the influence of his maternal uncle Mistawasis (Big Child), a leading figure in the Eagle Hill (Alberta) area. In 1873 Isapo-Muxika (Crowfoot), Chief of the Blackfoot, following a Plains Indian custom, adopted Pitikwahanapiwiyin to replace one of his own sons who had been killed in battle.

In August 1876 Pitikwahanapiwiyin, as headman of one of the River People bands, was influential enough to speak at the Treaty No. Six negotiations held at Fort Carlton. Pitikwahanapiwiyin emerged as one of the spokespersons for a group critical of the treaty. Though Treaty No. Six was amended to include a 'famine clause,' Pitikwahanapiwiyin continued to express concerns and agreed to sign the treaty on 23 August only because the majority of his band favoured it.

In the autumn of 1879, Pitikwahanapiwiyin, now chief, accepted a reserve and settled with 182 followers on 30 square miles along the Battle River about 40 miles west of Battleford. Frustrated by the government's failure to fulfill treaty promises, Pitikwahanapiwiyin became active in Indian politics: representing the Cree at inter-band meetings and acting as a spokesperson with the government. In July 1881 Pitikwahanapiwiyin acted as guide and interpreter during Governor-General Lord Lorne's trip from Battleford to Calgary. In June 1884, a Thirst Dance was held on the Poundmaker reserve to discuss the worsening situation of the Indians. By the middle of the month over 2,000 people had gathered. The Thirst Dance celebration was disrupted by the North-West Mounted Police pursuing an Indian accused of assaulting the farm instructor on an adjacent reserve. Violence between the Indian bands and the 90-man police force was averted by the peacekeeping efforts of Pitikwahanapiwiyin and Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear).

When news of the Métis success at Duck Lake reached the Poundmaker reserve in March 1885, Pitikwahanapiwiyin decided to utilize the unrest and fears of government agents to negotiate necessary supplies. Joined by the Stonies, the Cree went to Battleford. Arriving on 30 March, Pitikwahanapiwiyin and his people found the town deserted. Efforts to open negotiations with Indian Agent Rae failed. Hungry and frustrated, some of Cree and Stonies began looting the empty homes in the Battleford area, despite Pitikwahanapiwiyin's attempts to stop them. The next day the combined Battleford bands moved west to the Poundmaker reserve and established a large camp east of Cutknife Creek. Though Pitikwahanapiwiyin was appointed the political leader and chief spokesperson for the combined bands, a soldiers' lodge was also erected at the Cutknife camp. According to Plains Cree tradition, once erected the soldier's lodge, not the chief, was in control of the camp.

Lieutenant-Colonel Otter attacked the camp in the early morning of 2 May 1885. After seven hours of fighting, the Indians forced Otter to withdraw. At this point Pitikwahanapiwiyin stepped in and stopped the Indians from attacking the retreating troops. Following the Battle of Cutknife Hill on 2 May, Pitikwahanapiwiyin attempted to move the camp to the hilly country around Devil's Lake. The warriors leading the camp, however, prevented this retreat and began leading the combined tribes east to join Riel at Batoche. On 14 May, while passing through the Eagle Hills, the Battleford bands captured a wagon train carrying supplies for Colonel Otter's column. Once again Pitikwahanapiwiyin successfully intervened to prevent bloodshed and the twenty-one teamsters captured along with the wagons were taken prisoner.

Five days later the Battleford bands learned of the Métis' defeat at Batoche. Regaining control of the combined bands, Pitikwahanapiwiyin sent Father Louis Cochin to Major-General Frederick Middleton asking for his peace terms. On 26 May, Pitikwahanapiwiyin surrendered his arms and his followers at Fort Battleford. He was immediately imprisoned.

On 17 August 1885 Pitikwahanapiwiyin's trial on the charge of treason-felony began in Regina before Judge Richardson. Regarded as second in importance only to Riel's, the trial lasted for two days. After deliberating for half an hour, the jury returned a guilty verdict. Pitikwahanapiwiyin was sentenced to three years in the Stony Mountain Penitentiary in Manitoba. He served only one year before being released because of poor health. Four months later, while visiting his adopted father Isapo-Muxika on the Blackfoot reserve, he suffered a lung haemorrhage and died.

Chief Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear)

Mistahimaskwa was born around 1825 near Jackfish Lake, north of present-day North Battleford. His father, Black Powder, an Ojibwa, was the Chief of a small mixed band of Cree and Ojibwa and his mother was a member of one of these nations.

Mistahimaskwa began establishing himself as a leader in the late 1850s and early 1860s. In 1871 he was the leading chief of the Prairie River People and by 1874, headed a camp of 65 lodges (approximately 520 people). His influence rose steadily in the following years, reaching its height in the late 1870s and early 1880s.

Although he appeared at the negotiations, Mistahimaskwa refused to sign Treaty No. Six: he was the first major chief on the prairies to do so. Over the next six years, Mistahimaskwa continued to refuse treaty. Finally on 8 December 1882, faced with destitution and starvation, Mistahimaskwa signed an adhesion to the treaty. At this time his following had dwindled to 114 people.

In the late 1870s Mistahimaskwa tried to create a political confederation of Indian bands capable of forcing concessions from the government. From 1878 to 1880 he traveled through the Canadian North-West and Montana trying to unite the bands. In the 1880s Mistahimaskwa's efforts focused on uniting Cree bands and attempting to create an Indian territory in the Northwest through adjacent reserves. The government refused to grant contiguous reserves and did not respond to joint gatherings of Cree bands, such as the one organized by Mistahimaskwa at Fort Battleford in May 1884 to present Indian grievances. In June 1884, Mistahimaskwa hosted a Thirst Dance at the Poundmaker Reserve. The event, which was attended by over 2000 people, was disrupted by the NWMP and only the efforts of Mistahimaskwa and Pitikwahanapiwiyin (Poundmaker) averted violence.

As a result of the government's refusal to negotiate with him, Mistahimaskwa began to lose influence over the band's warrior society during the winter of 1884-1885. On 2 April 1885, Mistahimaskwa's band led by his son Ayimisis and the war chief, Kapapamahchakwew (Wandering Spirit), killed nine people at Frog Lake. Mistahimaskwa's efforts to stop the massacre failed. No longer in control of the band, Mistahimaskwa remained in the background counseling peace during the rest of the resistance. On 14 April Kapapamahchakwew moved to attack Fort Pitt. Mistahimaskwa successfully negotiated the surrender of the fort's 44 civilian inhabitants and the police evacuation. The band fought General Strange at Frenchman's Butte on 28 March, and again at Loon Lake on 3 June. Mistahimaskwa did not participate in the fighting on either occasion.

Mistahimaskwa surrendered at Fort Carlton on 2 July. He was brought to trial in Regina on 11 September. After deliberating for fifteen minutes, the jury found him guilty of treason-felony, and he was sentenced to three years at the Stony Mountain Penitentiary. Released in February 1887 because of poor health, Mistahimaskwa settled on the Poundmaker reserve where he died on 17 January 1888.

Sir Frederick Dobson Middleton

Sir Frederick Middleton is best remembered as the commander of the North-West Field Force which was sent to suppress the Northwest Resistance of 1885. Middleton was born on 4 November 1825 in Belfast, the third son of Major-General Charles Middleton and Fanny Wheatly. He was educated at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst and was given his first commission in 1842.

Middleton served in many parts of the British Empire, including Australia, New Zealand, India, Burma, Gibralter, and Malta. He distinguished himself as a staff officer in India, during the 1857-1858 Mutiny, and was recommended twice for the Victoria Cross. His overseas service included a stay in Canada (1868-1870) where Middleton married his second wife, Eugénie Doucet of Montreal. In the 1870s Middleton served as executive officer at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst.

In 1884, Middleton, now a Colonel, accepted the position of general officer in command of Canada's militia. This normally quiet position became a difficult one for Middleton when, at age 59, he had to assume the leadership of the suppression of the resistance in the Northwest Territories in 1885.

Middleton's approach was a cautious one. He faced considerable logistical difficulties and an army composed almost exclusively of poorly trained militia. He divided his forces into three, reserving for himself the main force which was to attack the Métis stronghold of Batoche. The Métis forces under Gabriel Dumont engaged Middleton's forces at Fish Creek on 24 April. Although the battle was something of a victory for the tiny Métis and Indian army, it was not decisive. Middleton proceeded with caution to Batoche. After a four day engagement, the greatly outnumbered and ill-equipped Métis were overrun on May 12. With the capture of Louis Riel on May 15, the surrender of Pitikwahanapiwiyin (Poundmaker), and with the recovery of whites held by Indians, Middleton returned home at the end of June.

Middleton was granted a gift of $20,000 from the Parliament of Canada and given a knighthood by Queen Victoria. He resigned as head of the Militia in 1890 when a select committee of the House of Commons criticized him for the misappropriation of furs from a Métis named Charles Bremner during the resistance. He returned to England where he was appointed keeper of the crown jewels. He died on 25 January, 1898.

William Dillon Otter

William Dillon Otter is often regarded as Canada's first true professional soldier. He was born in 1843 near Goderich Ontario. While working as a clerk in the 1860s Otter joined the militia with the Queen's Own Rifles and fell in love with the military way of life.

In 1866 he participated in the defence of Canada against Fenian raids at the Battle of Ridgeway. By 1883 he was able to secure appointment in the tiny permanent army by becoming commander of the infantry school at Toronto. With the outbreak of the 1885 Resistance, Otter was despatched to the Northwest Territories to assist General Frederick Middleton in the advance on the Métis stronghold of Batoche. However, upon news of the murder of white settlers at Frog Lake, Otter was placed in charge of a column that was to "relieve" the town of Battleford and the surrounding area from the threat of Indian attack.

Liberally interpreting Middleton's commands, Otter decided to seek out and engage the Cree and Stoney Indians who had been threatening Battleford under Chief Pitikwahanapiwiyin (Poundmaker). Otter met the Indian forces at Cut Knife Hill on 2 May and was routed. Only the intervention of Pitikwahamapiwiyin prevented the Indian forces from inflicting greater damage on Otter's retreating column. With the fall of Batoche, Otter assisted in the army's unsuccessful attempt to capture the elusive Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear).

Otter's military reputation was not harmed by his loss at Cut Knife Hill. He would serve in the South African War and become the first Canadian-born Chief of the General Staff. During World War I he was placed in charge of Canadian internment camps. He was knighted in 1913 and made a general in 1923.

In the early 1880s almost everyone living in the Northwest Territories had grievances against the Government of Canada. The native people had signed treaties which were supposed to compensate them for giving up claim to the whole of the territory and agreeing to settle on reserves and learn white-style agriculture. But the Government was reluctant to live up to its side of the bargain and tried to evade its responsibilities. Thus, people who were already unhappy at having to give up much of their traditional way of life were made more angry and desperate as the promised new way of life failed to materialise.

Although their actions at Red River in 1869/70 had won some major concessions from Ottawa, many of the Métis had moved farther west and settled in the Saskatchewan Territories. By the 1880s, settlers from Europe and Eastern North America were moving into the Saskatchewan and the Métis saw their traditional lifestyle threatened again.

The white settlers in the Territory were also angry and aggrieved. They accused the Canadian Government of operating the Territory solely for the benefit of Eastern Canadian business to the detriment of local interests.

By the middle of the decade all parties in the west were holding meetings, sending petitions and discussing political tactics for redress of their grievances against a government which seemed as uninterested as it was remote.

Many of the documents listed in the Bibliography reflect this general dissatisfaction. A search using the term "grievances" will retrieve material on all parties.

April 24, 1885: Lieutenant-Colonel William Otter relieves the 'siege' of the Fort Battleford without a battle. The Battleford bands have left the area and established a camp at Cutknife Hill.

April 26, 1885: Indians raid HBC post at Lac La Biche, Alberta.

May 2, 1885: Colonel Otter's column attacks Pitikwahahnapiwiyin's camp at Cut Knife Hill. Otter is forced to retreat to Battleford. Pitikwahahnapiwiyin prevents Indians from attacking retreating troops.

May 9 - 12, 1885: Battle of Batoche. Middleton decisively defeats the Métis force in a three day battle.

May 14, 1885: At Eagle Hills, Battleford Indian bands capture wagon train carrying supplies for Colonel Otter's column. Twenty-one teamsters are taken prisoner.

May 15, 1885: Louis Riel surrenders and is transported to Regina for trial.

May 26, 1885: Pitikwahanapiwiyn surrenders to General Middleton at Fort Battleford.

May 28, 1885: Mistahimaskwa's band and Major General T.B. Strange clash at Frenchman's Butte.

June 3, 1885: Steele's and Mistahimaskwa's forces engage in a skirmish at Loon Lake.

July 2, 1885: Mistahimaskwa surrenders to North-West Mounted Police at Fort Pitt.

July 6, 1885: Riel is formally charged with high treason

July 20 - August 1, 1885: Riel is tried and found guilty of treason. Judge Hugh Richardson sentences Riel to hang 18 September.

July 24, 1885: William Henry Jackson is found not guilty by reason of insanity. Jackson is sent to a lunatic asylum in Manitoba..

August 5, 1885: Sir John A. McDonald requests that murder charges be laid against the Indians involved at Frog Lake and in the killing of Payne.

August 13, 1885: Kapeyakwaskonam (One Arrow) tried on the charge of treason-felony, found guilty and sentenced to three years imprisonment .

August 14, 1885: A number of Métis involved in the rebellion plead guilty to treason-felony and receive prison sentences ranging from one to seven years.

August 17 - 19, 1885: Pitikwahanapiwiyin is tried on the charge of treason-felony, found guilty and sentenced to three years imprisonment .

September 9, 1885: The Manitoba Court of Queen's Bench rejects Riel's appeal.

September 11, 1885: Mistahimaskwa is tried on the charge of treason-felony, found guilty and sentenced to three years imprisonment .

September 25, 1885: Kapapamahchakwew (Wandering Spirit) is tried at Battleford and sentenced to hang.

October 5, 1885: Itka and Man Without Blood are tried, found guilty and sentenced to hang for killing Payne.

October 10, 1885: Five Indians are tried in Battleford for involvement at Frog Lake, are found guilty and sentenced to hang.

October 22, 1885: Judicial Committee of the Privy Council rules against Riel's appeal.

November 9, 1885: The Medical commission, created to examine Riel's mental condition, submits its report to the Prime Minister. The Commission is divided on question of Riel's sanity. Cabinet decides to proceed with death penalty.

November 16, 1885: Riel is hanged Regina.

November 27, 1885: Kapapamahchakwew and seven other Indians are hanged at Battleford.

A special thanks to the University of Saskatchewan for granting permission to use research material from it's library:

More information about the Northwest resistence and associated North American white supremacist racism can be found at:

Chief Poundmaker:

Chief Wandering Spirit:

Prime Minister John A. Macdonald's government oversees the mass execution of eight Cree:

President Abraham Lincoln authorizes the mass execution of 38 Lakota:

American Indian Genocide: