|

|

|

|

Traditional Mi'kmaq Chief Headdress

Created and modeled by Todd Labrador - Acadia Band

If you would like Todd to make a traditional headdress

for you, or other Mi'kmaw handicrafts, including Birch

Bark Canaoes, he can be contacted at:

toddlabrador777@outlook.com

Because some viewers may not be aware of Band name changes the old names are in brackets

Terry Richardson - Oinpegitjoig Band (Pabineau), N.B. - Andrea Paul ,Pictou Landing Band, N.S. - George

Ginnish, Natoaganeg Band (Eel Ground) N.B. - Sacha LaBillois, Ugpi'ganjig Band (Eel River Bar), N.B.

Darlene Bernard, Lennox Island Band, P.E.I. - Sidney Peters, Glooscap Band (Horton), N.S.

MI'KMA'KIK TERRITORIAL BOUNDS:

All of the Provinces of Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, the province of New Brunswick - north of the Saint John River, most of Quebec's Gaspe Peninsula, and Northern Maine

LANGUAGE: Mi'kmaw - Legislation to recognize Mi’kmaw as Nova Scotia’s first language was proclaimed today, July 17, 2022 by the Province and affirmed by the Mi’kmaq during a ceremony in Potlotek First Nation in Richmond County. The Mi’kmaw Language Act will take effect on October 1, 2022, Treaty Day and will support efforts to protect and revitalize the language. The legislation was passed by the legislature in April 2022.

Daniel N. Paul: “Although I think it is a nice gesture by the Province it only affirms what is in fact something that is true dating back to time immemorial: Mi’kmaw is the first Language of Mi’kma’ki, and the portion of Mi'kma'ki now known as Nova Scotia.”

The Europe of the 1600s was ruled over by ruthless aristocrats, who were firm believers in using terror tactics to terrorize their citizens into submission. The development of it’s societies saw “look after me first” become the cardinal rule for it’s people. This resulted in the establishment of class systems where people were allocated status, and were expected to kowtow and pay homage to their betters, and it saw the establishment of such things as debtors prisons, bedlam’s for the insane, poor houses for the poor, and so on. The masses were generally oppressed. There wasn’t much security for the elite either, they often plotted and schemed to depose one another, and murder to achieve higher status wasn’t unknown. In spite of paying lip service to paying homage to the Christian God, Greed was the God that many held supreme.

The Americas of that era also had several societies ruled over by Emperors, however, the vast majority of Indigenous American societies were democratic, the people ruled. The Mi’kmaq lived in such a society. The Mi’kmaw leader had no special perks and, without shedding blood, could be replaced by the People. Mi’kmaq leaders were great orators, this was the only means they had to influence the people to follow them. Honor was the cardinal rule that Mi’kmaq society operated under, and looking after the welfare of the entire community was the number one requirement of the citizens. All things were shared equally, there was no such thing as a desire for personal enrichment, greed in this respect was unheard of.

PATRIARCHAL

(NOTE: In modern times Mi’kmaw society has become co-equal, men and women jointly hold all political and management positions, as a matter of fact matriarchal and patriarchal have been replaced by co-equal in most Indigenous cultures in Canada.)

Directly opposite to the governing system of Iroquoian societies, which have Matriarchal Clan Systems of government, where Clan Mothers appoint leadership, Algonquian societies were Patriarchal. Thus, in Mi'kmaq society, wise men with impeccable reputations of honorable conduct, and proven hunting abilities, had to compete for appointment by the People to fill leadership positions. When selected, a man could serve for life, provided he conducted himself with dignity and humility. Hereditary Chiefs were not part of the system.

POLITICAL STRUCTURE

Democratic - Consensus Based: Chiefs and other leaders were selected by the People - hereditory Chiefs were not part of Mi'kmaq society. Sieur de DiPreville wrote about what was required of men who aspired to fill the Nation's leadership positions:

"The cherished hope of leadership inspires resolve to be adept in the chase. For it is by such aptitude a man obtains the highest place; here there is no inherited position due to birth or lineage, merit alone uplifts. He who has won exalted rank, which each himself hopes to attain, will never be deposed, except for some abhorrent crime. No wise noteworthy are the honours paid his high estate, for he is merely first among a hundred..., more, or less, according to the size of his domain."

RELIGION

The Great Spirit's directives were the Mi'kmaq Nation's eternal light. The People believed that His dominion was all-inclusive, and that He encompassed all positive attributes-love, kindness, compassion, knowledge, wisdom etc., and that He was responsible for all existence and was personified in all things-rivers, trees, spouses, children, friends etc. No initiatives were undertaken without first requesting His guidance. His creations, "Mother Earth" and the Universe, were accorded the highest respect. Religion was blended into daily life-it was lived. Nature, as was the case with most American civilizations, supported Mi'kmaq religious beliefs.

GOVERNMENT:

The Mi'kmaq occupied a large area of northeastern North America for approximately 5,000 to 10,000 years. The Nation's original territory covers most of what today comprises Canada's Maritime Provinces, a good part of eastern Quebec, and northern Maine.

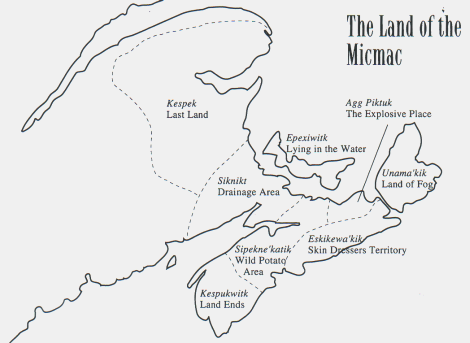

The territory was divided into seven distinct "Districts." Their names were: Kespukwitk, Sipekne'katik, Eskikewa'kik, Unama'kik, Epekwitk Aqq Piktuk, Siknikt, and Kespek. The English translations are shown on the map and are as close as one can come to conveying their true meaning in that language.

Citizens lived in small villages which were populated by fifty to five hundred people. The number of villages and total population within each District is subject to conjecture.

District governments comprised a District Chief and Council. The Council included Elders, Band or Village Chiefs, and other distinguished members of the community. Among these leaders the Elders, both men and women, were the most appreciated. The Mi'kmaq held them in the highest regard and accorded them the utmost respect. Their advice and guidance was considered to be essential to the decision-making process, and thus no major decision was made without their full participation. A District government had conditional power to make war or peace, settle disputes, apportion hunting and fishing areas to families, etc. Thus, a District may be likened to what we call a "country" today.

At an unknown point in the distant past a Grand Council was established by the Districts to coordinate the resolution of mutual problems, promote solidarity, and act as a dispute mediator of last resort when problems arose among them. District Chiefs elected one of their number as Grand Chief. The Grand Council's influence was derived from the esteem in which the District Chiefs were held. The Council did not have, beyond friendly persuasion, any special powers other than those assigned to it by the Districts. At sittings of these Councils, all men and women who wanted to speak were heard, and their opinions were given respectful consideration in the decision-making process. In modern terms, the Grand Council may be compared to the British Commonwealth of Nations, which also has no real powers other than persuasion.

The independence of each District was in place when treaties were signed between the Mi'kmaq and the British. The Treaty of 1725 was ratified at Annapolis Royal on June 4, 1726 by the Chiefs and Head men of several Districts that were present that day. Consequent Treaties, related to the Treaty of 1725, for example the Treaty of 1752, were negotiated by each District and the British. Paragraph 3, of the 1752 Treaty includes this requirement of Sipekne'katik District Chief Kopit (translates Beaver), Christian name "Jean Baptiste Cope":

"That, the said Tribe shall use their utmost endeavours to bring in the other Indians to Renew and Ratify this Peace...."

CULTURE DESCRIPTION

Exaggerated reports about the facial features, clothing and customs of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas by early Norse and Viking travelers were probably the reasons pre-Columbian contacts promoted stories in Europe about a strange people-non-humans, hairy monsters, subhumans-inhabiting a far-off land. Probably not much thought was given to the prospect that they could be intelligent and civilized human beings, an existence well documented by early European colonial scribes.

Prior to European settlement the Mi'kmaq lived in countries that had developed a culture founded upon three principles: the supremacy of the Great Spirit, respect for Mother Earth, and People Power. This instilled in them a deep respect for the laws of the Creator, the powers of Mother Earth and the democratic principles of their society. As a result they enjoyed the benefits of living in a harmonious, healthy, prosperous and peaceful social environment.

The nature of Mi’kmaq society, which included sharing and free expression, was so advanced in the establishment of equitable human rights principles that greed and intolerance were all but unknown. Thus, the European concepts which separated people into a distinct hierarchy based upon birth, colour, race, lineage, religion, profession, wealth, politics and other criteria would have seemed to them unbelievable. This absence of biases about the differences of others is one of the best indicators of how far advanced Mi'kmaq culture was in the development of human relations.

The lofty plateau the Mi’kmaq had reached, where all people were accepted as equals, is an ideal that modern society is still working towards. In retrospect, if the Mi’kmaq and most other Native Americans had not reached this stage by 1492, European colonization could not have occurred. Instead, because of their skin colour and strange religions, Whites would have been either enslaved, repulsed, or exterminated upon arrival.

CULTURAL BEHAVIOUR

Bernard Hoffman, in a doctoral thesis he wrote in the 1930s, gives a description of the cultural behaviour of the Mi'kmaq which shows that they were extremely compassionate and offered a civilized welcome to strangers:

"The behaviour pattern requisite of any Micmac was such as too virtually eliminate any overt and direct forms of aggression. The ideal man was one who was restrained and dignified in all his actions, who maintained a stolid exterior under all circumstances, who deprived himself of his possessions to take care of the poor, aged, or sick, or the less fortunate, who was generous and hospitable to strangers...and brave in war."

Hoffman's assessment of the Mi’kmaq character is well supported by the records left behind by explorers, missionaries, politicians, and others from that era.

MI'KMAQ WELCOME

A speech by Daniel N. Paul to the Nova Scotia Tourist Association, November 16, 2003

Welcome my friends, I hope you have a pleasant visit!

I’ll start my discourse about Mi’kmaq welcome by relating how it came to be that my people always welcomed visitors to the land of the Mi’kmaq with open arms - a practice dating back into infinity. In fact, in pre-Columbian days, they often entertained visitors and traders arriving from other First Nations located across Turtle Island - our name for North America.

Such hospitality resulted from the early indoctrination of children with the worthy social values of a people friendly civilization, which our ancestors had developed with great wisdom over the ages.

One of the most important of these values, taught to the young by the Elders, was that the Great Spirit created all people equal - which prevented the development in their minds of biases against people who were different. Thus, intolerance was not a vice harboured in the hearts of the Mi’kmaq.

In view of this, it should come as no surprise to anyone that during 1604 my ancestors welcomed strange looking visitors to their land. When Champlain and ship’s company landed on our shores, in spite of their white skins, bearded faces, strange clothing and behaviour, they were warmly welcomed by the Mi’kmaq as brothers and sisters. The most important among the Mi’kmaq Peoples values, which made hospitality to strangers a must, was personal honour. It was an individuals most valued personal asset. To fail to keep one’s word, or to be disrespectful of others, was punishable by being ostracized by peers. A fate considered worst than death.

Therefore, children were taught to be generous and non - confrontational with each another, or with strangers. This is how Bernard Gilbert Hoffman, a history researcher, described it:

“The behaviour pattern required of any Micmac was such as too virtually eliminate any overt and direct forms of aggression. The ideal man was one who was restrained and dignified in all his actions, who maintained a stolid exterior under all circumstances, who deprived himself of his possessions to take care of the poor, aged, or sick, or the less fortunate, who was generous and hospitable to strangers . . .”

Historian, Cornelius J. Jaenen, provides an excellent example of how Europeans were flustered by such civil behaviour. He, when discussing First Nations Peoples attitudes toward religious conversion, relates that Calvin Martin found it was sometimes difficult to distinguish between genuine conversion and a tolerant assent to strange views. Martin’s description:

“Such generosity even extended to the abstract realm of ideas, theories, stories, news and teachings. The Native host prided himself on his ability to entertain and give assent to a variety of views, even if they were contrary to his better judgement. In this institutionalized hospitality, lies the key to understanding the frustration of the Priest, whose sweet converts one day were the relapsed heathens of the next. Conversion was often more a superficial courtesy, rather than an eternal commitment, something the Jesuits could not fathom”

Now for something that may seem incredible to you, especially when compared with modern society’s values, our ancestors had no notion of greed. All shared alike. It was what can be described as a “you” society, performing at it’s best, no personal enrichment. Thus, greed, an insidious evil that is still bedeviling modern society, was not a problem for them. The absence of it made it easy for the Mi’kmaq to give gifts of precious possessions to visiting friends and strangers. Such was a fundamental part of Mi’kmaq life. Jaenen explains:

“The French often commented on the absence of a sense of exclusive ownership of goods and lands among both nomadic and non-nomadic tribes. The observation of an officer at Louisbourg is typical of such comments: "They are very uncaring about paying the debt they contract, not from natural dishonesty, but from their having no notion of property, or of owing a debt. They will sooner part with all they have, in the shape of a gift, than with anything in that of payment. Honours and goods being all in common amongst them, all the numerous vices, which are founded upon those two motives, are not to be found in them.”

This is the type of welcome that Nova Scotians must endeavor to bring to the fore again. Visitors must be treated with consideration and respect. They must never be viewed as passers through, who will never return, and whose money can be taken without giving them excellent value in exchange.

When they come, treat them like beloved visiting members of the family circle, give them quality value for their money. This will cause them to return and cause them to encourage others to come visit. Warm feelings of satisfaction instilled in visitors by caring hosts is what a healthy tourist industry is built from.

Such a universal new approach is a must. I say this because I’ve often seen in recent years, like most of you probably have, the quality of the offerings of the province’s hospitality industry to guests diminished in favour of a better profit line. In fact, many have been so successful at this endeavour, that they have, in pursuit of the paper profits offered by penny-pinching efficiency experts, put themselves out of business.

You, my friends, Nova Scotia’s hosts, must be cautious not to be lured by such corporate short term thinking –– the investments each of you input into the hospitality and welcome industry will return a hundred fold if visitor satisfaction is high.

It’s wise to remember: The best way to make and keep a new friend, is to lavish on him or her the very best you can offer!

In closing, I strongly urge you to try the Mi’kmaq way. It’s tried, tested and proven. If you need proof of the veracity of this declaration about the effectiveness of Mi’kmaq hospitality look around you - we have close to a million visitors abiding in this part of Mi’kmaq land, who show no sign of preparing to leave!

All the best!

Daniel N. Paul

Wiklatmu'j - Stone People

By George Paul - Eskasoni, March 27, 2004

Edited by Daniel N. Paul

Most cultures have tales about their own little people. For example, the Irish have Leprechauns and we, the Mi'kmaq, have the Wiklatmu'j. In our folklore our little people, because they live in mountain caves, are known as the Stone People. In most cases, fictitious tales told by parents about the deeds they do, whether bad or good, are told to help children take the right path, or protect them from misadventure.

However, folklore or not, many Mi'kmaq people do believe that the Wiklatmu'j exist. And, they have a good idea about how they look, and how they act.

This is how historical writers describe them: They are small, but do big work. They live and dress like the old-time Mi'kmaqs and they speak Mi'kmaq. They live on Quebec's Gaspe' Peninsula, on Tracadegash Mountain, and on Nova Scotia's Cape Breton Island. They have small arms and legs and big bodies like bullfrogs. Like other supernatural beings, they can help, for instances, by giving a man furs, or warning him of coming evil, or harm, by performing bad tricks around the house and barn.

The Wiklatmu'j are only as tall as a three-year-old child, but are as swift as lightening. They are strong and sound like birds when talking to each other. They dress light, go barefoot, and smoke a pipe. The only apparent difference between the male and female, except, of course, biological difference, is their hair. They live in the woods, write on stone, eat meat, berries and fish, and like to dance, sing and play.

One thing you don't do is disrespect the Wiklatmu'j. They are strong and they can take you down no matter how big you are.

The legend of the Wiklatmu'j still remains strong in Mi'kmaq communities, especially in Eskasoni. Thus, not surprising, Eskasoni's Mi'kmaq Center of Excellence has, for our enjoyment and preservation of our birthright, collected many stories of the people's encounters with the Wiklatmu'j. Some are modern, while others are more than 100 years old.

One old story is about a Mi'kmaq man who went hunting. He was travelling deep in the forest when he came upon two little people who asked, "What are you looking for, and where are you going?" The hunter said, "I'm looking for fur, and not going anywhere in particular."

As it was getting late, the Wiklatmu'j, showing a fine sense of hospitality, invited the hunter to stay overnight with them. To make up for taking him away from his work they promised that they would give him fur when he left. Accepting the invitation, he followed them through a door into a cliff.

Entering their village, the hunter was given a joyous welcome. He enjoyed their hospitality so much, especially the variety of fascinating games he played with them, that he stayed for two of their days. When the visit was over, as promised, the Wiklatmu'j gave him two bundles of fur to take home. When he arrived home, because he had been gone for two years, the family was shocked to see him, they had sadly come to believe that he had died in the forest.

A more recent story is about a girl name Mary Ann from Eskasoni. She lived near the beach and had learned about the Wiklatmu'j from her father. One day, near noon, in spite of the fact that her mother had warned her many times not to go there, she was playing at the top of a cliff overlooking the lake. She looked down and saw someone moving around near the shore.

Curious, she began to climb down to see who it was when, about half way down, she met a little man, a Wiklatmu'j. It gave her such a fright she fainted.

When she awoke, she was back on top of the cliff. Frightened, she started running for home and didn't look back to see if the Wiklatmu'j was following. Upon arrival she was out of breath and had a sore side from running so fast. When her mother saw her, she noticed that her hair was all messed up and asked, "Where have you been, your hair is in such a mess?"

Mary Ann told her mom what had happened. Her mother responded: "That's what happens to little girls when they disobey their mothers, you're lucky the Wiklatmu'j didn't take you with him." Mary Ann never again disobeyed her mother, or went back to the cliff alone.

The before mentioned are just a few of the scores of fascinating stories about individual Mi'kmaq encounters with the Wiklatmu'j, I hope you enjoyed them!

Direct descendants of the North American Paleo people, the Mi'kmaq, who have inhabited Nova Scotia for approximately 10,000 years, are part of the loose Wabanaki Confederation, which includes, among others, the Maliseet of New Brunswick and the Penobscot of Maine: they are part of the widespread Algonquian group, which contains many different languages and cultures.

Pre Colonization

Mi'kmaq territory included all of what is now Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, and the Gaspe of Quebec, New Brunswick - north of the Saint John River, northern Maine and probably a part of Western Newfoundland. Prior to colonization, like other First Nation people across North America, they practiced a religion that was based on Mother Nature, deeply tied to the land. Mythology also played an important part in spiritual life. Their society was patriarchal.

For centuries, the Mi’kmaq established both winter and summer settlements. Summer settlements tended to be along the shoreline where they fished, gathered shellfish, and hunted seals and whales. In the winter, most moved inland, setting up settlements in sheltered forested areas. They hunted (moose, bear, caribou, and smaller game) for food and clothing, gathered wild berries, and used plants and herbs for teas and medicinal purposes.

They lived in conical birch bark wigwams: birch bark was also used to make canoes in which to travel the waterways. The Mi’kmaq were also at home on the sea, travelling in ocean-going versions of the light birch bark canoes used for the inland waters. In 1659, a French priest wrote ”It is wonderful how these savage mariners navigate so far in little shallops (small, open boats) crossing vast seas without compass, and often without sight of the sun, trusting to instinct for their guidance”. More likely, they trusted to Mother Nature’s guides, currents, winds, Sun and Moon, etc. for directional guidance.

It is not over-romanticizing things to say that the Mi’kmaq respected their environment and only killed, took or used what they needed. When Europeans first settled Nova Scotia, the natural resources were virtually untouched. Quite how many Mi’kmaq lived in what is now known as Nova Scotia, prior to the arrival of Europeans, is a matter of speculation, with estimates ranging from a ridiculous 3,000 to a more realistic 200,000.

European Contact

When the French settled Port Royal (see page XXX) they were befriended by the Mi’kmaq, and for the next century and a half, the friendship stayed strong. The name Mi'kmaq is thought to have derived from “nikmaq”, meaning "my kin-friends," a greeting used to them by early French settlers. The Mi’kmaq referred to themselves as L’nuk, “the people”.

The Mi’kmaq acted as guides for the settlers who learned much about living off the land from them - how to make fish-weirs, and eel-traps, how to ice-fish, which wild berries were safe to eat and how to prepare them, how to cure and prevent scurvy, and more.

Always somewhat xenophobic, the English saw how well the Mi’kmaq got on with the French, but they distrusted and feared them from the start. Thus, instead of accepting the Mi’kmaq as a free and independent People, as the French did, they opted for subjugating them by brute force

The Mi’kmaq began to convert to Christianity in 1610. That year, Chief Membertou and his family were baptized by the French. The Mi'kmaq gradually altered their way of life, abandoning many of their earlier customs and focusing on gathering furs and hides for trade purposes. The French gave them weapons, and both French and English passed on diseases such as smallpox which killed hundreds – if not thousands.

In 1749, Governor Edward Cornwallis, founder of Halifax, put a bounty on the head (or scalp) of every Mi’kmaq, man, woman or child. The amount of the bounty was increased the following year.

In the 18th century, various peace and friendship treaties were signed between the English and Mi’kmaq, and a Royal Proclamation by King George III in 1763 promised “that the several Nations or Tribes of Indians with whom We are connected, and who live under our Protection, should not be molested or disturbed in the Possession of such Parts of Our Dominions and Territories as, not having been ceded to or purchased by Us, are reserved to them or any of them, as their Hunting Grounds”.

Often caught between the French and the English power struggle for North America, the Mi’kmaq suffered a similar fate to that of just about all the First Nations and Native Americans across the continent. They were robbed of their land, persecuted, forced to live with virtually no rights, and herded onto reserves.

Their culture and heritage was suppressed, too: for decades, the federal government actively suppressed Mi’kmaq (and all First Nations) traditions. For example, in 1885, religious ceremonies were prohibited. In 1927, Canadian government legislation forbade aboriginals in Canada from forming political organizations, as well as practicing their traditional culture and language. Also, from the time the English took over the colony from the French in 1713, a policy of assimulation was adopted by them to try to exterminate First Nations Peoples.

Once free to roam the entire region, in the 19th century the Mi’kmaq were confined to about 60 locations, both on and off reserve, dotted about the province. In the 1940s the Canadian implemented a Centralization Policy, which mandated that they be moved without their will to just 2 reserves, Eskasoni and Shubenacadie. Young Mi’kmaq children were taken away from their families and taught the “white man’s ways”, to integrate them into mainstream society - and rapidly lose the culture and heritage of the Mi’kmaq’s ancient way of life.

The Mi’kmaq in the 21st century

Today, there are approximately 15,000 Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia. They are divided into 13 Mi’kmaq First Nation Bands, whose members have usufructuary rights to approximately 28,000 acres of mostly unproductive land (The title of Reserve land is held by the Canadian Crown). About 60% live on 32 widely scattered Indian Reserves.

A hopeful sign for their preservation, young Mi’kmaq are rediscovering their language, culture and heritage. The Mi’kmaq have used their Aboriginal Rights, supported by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, to reclaim their hunting and fishing rights – albeit to the annoyance of some in the heavily regulated mainstream fishing industry. The visitor can learn some interesting things about Nova Scotia’s original inhabitants, their history and heritage at three cultural centres: Bear River (see page XXX), Glooscap (see page XXX) and Wagmatcook (see page XXX).

After centuries of suffering suppression, persecution and attempted genocide, there are attempts to put the record straight: Daniel N. Paul’s “We Were Not the Savages” is a must read for anyone interested in the real history of the province. The author is also behind a petition ( ) to rename all the province’s public entities, which were named in honour of colonial British Governor Edward Cornwallis - who founded Halifax in 1749, and twice by proclamations, in an effort to exterminate them, offered bounties for the scalps of Mi'kmaq men, women, and children, and any assisting them.

Please visit the following addresses, just click on any of them, they provide short descriptions of Mi'kmaq social and political structures, treaties, British scalp proclamations, Acadian relationship, etc.

First Nation Law - Aboriginal Law

Mi'kmaq Villages - Mersey River

Talking Circle - First Nations

British Outlaw Acadian - Mi'kmaq Contacts

Mi'kmaq Hostages - English Justice

Treaty Of 1725 Ratified - June 1726

Treaty Of 1725 - Liability Clause

British Scalp Proclamation-1744

British Scalp Proclamation - 1749

Great Britain Rescinds Scalp Proclamations - 1749 and 1750

British Mi'kmaq Treaty Of 1752

British Scalp Proclamation-1756

Mi'kmaq Nation - Poverty Stricken

Mi'kmaq people in traditional dress and Mi'kmaq artifacts preserved by the Nova Scotia Museum

North and South American IndianFood Sources and Cuisine

In view of the revelations of the horrors suffered by children in Catholic run Indian Residential School I believe the time has come for the Mi'kmaw Nation to have a distinctive Mi'kmaq flag. The present flag was designed by a Caucasian Catholic priest and is of European content. Click to read about the possible origins of the present flag, the Templar Battle Flag: Templar Battle Flags The new one raised must be of truly Mi'kmaq origin and designed by Mi'kmaw artists. To this end and in support of the proposal I offer the following opinion piece I wrote for Mi’kmaq/Maliseet Nations News in 2010:

Celebrating European Colonization

By Mi'kmaw Elder Dr. Daniel N. Paul, C.M., O.N.S.

November 16, 2010

What we the citizens of the First Nations of the Americas need to do, in order to achieve effective self government, is what other marginalized and oppressed people have done throughout history, chart a course built on our cultural heritage, which would return to us the solid effective self-government procedures that our Peoples had developed, implemented and enjoyed before the European invasion.

The summer of 2010 saw an event happen in Nova Scotia that happens far too often throughout the Americas, Indigenous Peoples celebrating with European institutions, in particular European royalty and European Christianity, the invasion of the two Continents by Europeans. In July of last summer, such a celebration occurred in the Maritimes, the Mi'kmaq feted the English (British) Crown, as represented by Queen Elizabeth II, and representatives of the Roman Catholic Church. During colonial times these two European institutions were responsible for the destruction of Mi'kmaq civilization as our ancestors knew it, the loss of our country, and the near extermination of our People. I credit such a happening with the fact that our People are largely unaware of the horrors that these two institutions visited upon the Mi'kmaq during European colonial times, and other First Nations of the Americas.

When one takes into account that the true history of the European invasion of the Americas, which relates the barbaric attacks against all of the First Nation civilizations of the two Continents, which were, in the face of far superior European armaments, almost helpless to defend themselves, is mostly unavailable, the before mentioned statement is understandable. The true history, which is not taught in schools, but is readily available if desired, relates that over the passage of time these barbaric assaults resulted in many Indigenous civilizations being exterminated altogether, and the remaining civilizations reduced to near ruin, millions dead, virtually all of their territorial lands, resources, and property stolen, and most survivors today living in destitution. In place of the truth, we get a diet of lies, which is willful blindness on the part of the descendants of the invaders. But this can now be changed, we ourselves can collect the truth, and teach the truth, in particular to our own Peoples.

The before mentioned explanation I've given for why some of our People, and leaders, would celebrate the European colonial invasion, and consequent appropriation of our countries with the two institutions mentioned, and the imposition of foreign ideals, is why I wrote a First Nations History Book and entitled it We Were Not the Savages (I encourage all to read it). It's my attempt to set the record straight. I did so because the demonizing colonial propaganda, which dehumanized the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas by depicting them to be bloodthirsty barbarian savages, and is the root cause of the systemic racism that stigmatizes Indigenous Peoples today, is still widespread, and, indefensibly, there is no concerted effort being made by the descendants of the invaders to set the record strait.

Before I go further, I'll provide some information on what the European invaders used during their colonization of the Americas to try to legitimize and justify their barbarity. The following is only an overview, only a book on the subject can relate the full story.

The origins of the Doctrine of Discovery can be traced back to a Papal Bull (proclamation) issued by Pope Nicholas V in 1452. In it he proclaimed that it was permissible for Christians to claim lands held by non-Christians because only Christians were entitled to hold lands. In 1493, one year after the barbarian Christopher Columbus got lost and landed in the Americas, Pope Alexander VI extended to Spain the right for it to conquer newly-found lands by issuing the papal bull Inter Caetera. This was after Christopher Columbus had already begun appropriating for Spain the lands of the Indigenous People of the Americas. Arguments between Portugal and Spain led to the Treaty of Tordesillas, which clarified that only non-Christian lands could thus be taken, as well as drawing a line of demarcation to allocate potential discoveries between the two powers. It must be noted that in spite of their hatred for the Catholic Church, European Protestant Nations adopted the warped Bulls of the Popes with great enthusiasm, and applied them as enthusiastically as the Catholics did when stealing Indigenous lands.

The Doctrine of Discovery was used when France claimed the land of the Mi'kmaq, which they christened Acadia. In 1618, Marc Lescarbot, a French lawyer, articulated how this warped Christian law legalized France's right to Acadia (now the Canadian Provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island): This, by the way, was eight years after Chief Membertou had converted to Christianity.

"The earth pertaining, then, by divine right to the children of God [Christians], there is here no question of applying the law and policy of Nations, by which it would not be permissible to claim the territory of another. This being so, we must possess it and preserve its natural inhabitants, and plant therein with determination the name of Jesus Christ, and of France."

Thus, in 1713, at the end of one of their numerous wars, England and France signed the Treaty of Utrecht, which, unknown to our ancestors, included a provision that transferred the lands of the Mi'kmaq and other First Nations to England.

In view of the White supremacist attitudes prevailing at the time, the fact that Amerindian Nations, including the Mi'kmaq, were left out of the treaty negotiations, not even made aware of its signing, should come as no surprise. A letter from Governor T. Caulfield to Vaudreuil, dated May 7, 1714, attests to the fact that the Mi'kmaq had been left in the dark: "Breach of the treaty of peace and commerce committed by Indians under French government upon a British trading vessel at Beaubassin. Enclosed letter from Pere Felix, giving the Indians' excuse, i.e., that they did not know that the treaty was concluded between the two crowns, or that they were included in it...."

Finally, in 1715, the Mi'kmaq were enlightened. At a meeting with the Mi'kmaq Chiefs two English officers informed them that France had transferred them, and the ownership of their land, to Great Britain via the Treaty of Utrecht, and that King George I was now their sovereign. The Mi'kmaq responded, in no uncertain terms that they did not come under the Treaty of Utrecht, would not recognize a foreign king owning their country and would not recognize him as having dominion over them. The Chiefs then clarified for the English that they had never given over ownership of their land to the French King, or considered themselves to be his subjects, and therefore he had nothing to transfer. With no agreement, open hostilities between the Mi'kmaq and the English resumed. Thus, the die was cast for close to fifty more years of conflict, broken, from time to time by occasional periods of uneasy truce.

After the Mi'kmaq learned that the French had claimed their land and, unbeknownst to them, transferred their territories to Great Britain by treaty two years earlier, the Mi'kmaq directed protests to St. Ovide de Brouillant, Louisbourg's military commander in 1715, and after September 1717, Governor. He responded: "He [the French King] knew full well that the lands on which he tread, you possess them for all time. The King of France, your Father, never had the intention of taking them from you, but had ceded only his own rights to the British Crown." In view of Marc Lescarbot's 1618 legal opinion that France was the owner of Mi'kmaq lands, because the Mi'kmaq were not Christians, and the Treaty transfer provisions, one can easily conclude that Ovide told a bald faced lie to continue France's alliance with the Mi'kmaq.

In the future, before we celebrate anything with the Catholic Church that happened during European colonial times, the Pope should be asked to come to the Americas and publically revoke the Papal Bulls that the European invaders used to steal the lands of the Indigenous Peoples of the two Continents, apologise for the tens of millions that were killed by the European invaders under the umbrella of the Bulls, and the loss of our freedom. And, above all, use the moral authority of his office to pressure the Eurocentric countries that were created in the Americas as a result of the invasion, to begin a process of writing history as it transpired, and discontinue the fairy tales that now pass for the history of the Americas.

After 1713, Great Britain was hell bent and determined to subjugate the Mi'kmaq and reduce them to beggars in their own land, or exterminate them all-together. Every barbaric means available was put to use to realize it's goal.

The most reprehensible of the methods selected by the British colonial governors of Nova Scotia were proclamations for the scalps of Mi'kmaq men, women and children, a practice that was widely used by British Governors before to decimate, and in several cases exterminate entire Tribes in what is now the eastern states of the United States of America.

Three proclamations for Mi'kmaq scalps were issued by Nova Scotia's British colonial governors. During 1744, the Mi'kmaq had the British fort at Annapolis Royal under siege, which caused the colony's Governor, Paul Mascarene, to request military assistance from the British Governor of the Massachuetts Bay Colony, William Shirley. On November 2, 1744, Shirley responded by declaring war on the Mi'kmaq, and their allies. The war declaration included a provision that provided that cash payments would be paid to those who harvested the scalps of Mi'kmaq men, women and children, and for the scalps of any who were assisting them. Captain John Gorham, who commanded Gorham's Rangers, was sent to Nova Scotia with his men to enforce the declaration. Their barbarities terrified all, including many British subjects.

Shortly after June 21, 1749, when Governor Edward Cornwallis arrived in Nova Scotia to found a settlement of suitable Protestants settlers at Chebucto Harbour, later renamed Halifax, he had English officers meet with the Mi'kmaq Chiefs to inform them once again that the King of England owned their land, and as the owners they were going to start building English settlements. In response, on September 23, 1749, the Mi'kmaq renewed their declaration of war against the British.

On October 1, 1749, Governor Cornwallis convened a meeting of his colonial military government, aboard HMS Beaufort, at anchor in the harbour, to decide upon a response to the Mi'kmaq declaration of war. It was decided not to declare war in return upon the Mi'kmaq, but to treat them as bandits, and offer a monetary reward for their scalps. Thus, on October 2, 1749, Cornwallis issued a proclamation that specified monetary rewards that would be paid to British Subjects that harvested the scalps of Mi'kmaq men, women and children. Geoffrey Plank, a history professor at the University of Cincinnati, labels it "a time when it was a capital offence to be a Mi'kmaq." The stated intent of the policy was to exterminate the Mi'kmaq. The following year, although scalps were being brought into British forts for payment, they apparently were not coming in fast enough, on June 21, 1750 the monetary reward was increased five fold. Cornwallis was removed as governor in 1752, however, before departure he, on July 17, 1752, revoked his bounty proclamations. Obliviously, as I'm writing this in 2010, his extermination plans failed!

Another scalp proclamation was issued in 1756, by Governor Charles Lawrence, this one was only for males over 16 years. It has not been repealed by an Act of Parliament.

On June 25, 1761, some of the Chiefs of the Mi'kmaq Nation gathered at the Governor's farm in Halifax and participated in a Burying of the Hatchet ceremony with British Governor Jonathan Belcher, and also signed several Peace and Friendship Treaties with him. The treaties were afterward ignored until the 1980s, when the Supreme Court of Canada ruled they were valid documents.

From 1761 onward the remaining Mi'kmaq were reduced to poverty, and suffered from starvation and malnutrition, which made any diseases they contracted almost always fatal. In the mid 1800s the situation was so bad, and the population was dwindling so fast (around 1400), that it caused two of the colony's Indian Commissioners, Joseph Howe and Abraham Gesner, to make predictions that the "Tribe would be only a memory if corrective action were not taken." After which, assistance increased somewhat, but did not end starvation.

When Canada was created in1867, by an Act of the British Parliament labelled The British North America Act, the federal government was given responsibility for Indians and Indian lands. Starvation was reduced considerably, however, malnutrition ran rampant up until the 1940s - the remaining population was somewhere around 1500 - to 2000. Finally, after 1946, vastly improved health care and better food supplies provided by the Feds stabilized the population and it started to increase. As a result, today there are somewhere around 25,000 Mi'kmaq. If proper assistance had been provided by the British Colonial Government after 1761, and by the Canadian government after 1867, the population of the Mi'kmaq today might well be half million or more.

In view of the before-mentioned, it would be only proper if all the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas put off any future celebrations with the English Crown, and other European governmental and social institutions, until such time as the Queen, or one of her successors, and other European leaders, come to the Americas and make full and open apologies to us for the horrors that their colonial ancestors inflicted upon our ancestors and their descendants!